History—the Hollywood Way

Written by Kiersten Conner-Sax | Posted by: Anonymous

The comment sounds glib, but E.T. was a good movie, as was Jaws, as was Raiders of the Lost Ark. After watching Amistad, though, I felt quite certain of something I had heretofore only supposed: Steven Spielberg needs to get over himself. He seems to be on a quest to edify the public as to the positive side of human evil by displaying the shining exception in the middle of the horrific rule. First, in Oskar Schindler, we met the only actually good German to emerge from the holocaust. Now, it’s a bunch of quasi-colonial Americans who stand up against slavery and defeat it through the courts, proving that the US justice system works, gosh darn it, and would have worked if it hadn’t been for those pesky Southerners. It’s as if Spielberg is saying that slavery, the continuing blight of American society, was merely an aberration that had nothing to do with the good men who framed our constitution. (Southerners aren’t real Americans; did you ever see a plantation owner in a powdered wig?) The ur-American conscience, embodied in these Disneyfied New England Puritans, is clear.

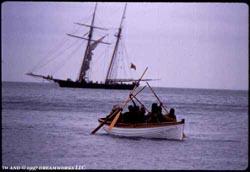

Spielberg’s film tells the story of a group of Africans captured in Sierra Leone and transported to the New World aboard the slave ship Amistad. After one man (later to be called "Cinque") breaks free of his chains, the Africans "mutiny" and kill the ship’s crew, with the exception of the navigator and his assistant. The navigator tricks the Africans into thinking he is taking them home, only to land near Long Island Sound. Once again, the Africans are captured and imprisoned. The film turns on the ensuing trial to sort out the legal claims of various people to the "property" aboard the Amistad and conflicting charges of piracy and murder.

The film opens with a striking and beautiful shot of Cinque, lit by lightening, working himself free of his chains. The following scene in which the Africans murder the Cuban crew and take control of the ship is the most powerful in the film. Unfortunately, Amistad peaks there, five minutes into the three hour story, and the flashes of lightening, overused, quickly began to remind me of strobe lights flickering at a junior high school dance.

From that point on, everything in Amistad felt wrong to me, from the requisite John Williams score to the sun drenched final shot. Spielberg can’t wring much action out of the courtroom drama, and these scenes are broken up with scenes of the prisoners singing and dancing, first in protest, then in celebration—which struck me as the worst kind of cliché. On a different point, why was Morgan Freeman given top billing over Djimon Hounsou, who appears in almost every scene? Moreover, why was Freeman’s character even in the film? Or Stellan Skargaard’s? Their characters argue over the purpose of the trial, hire a lawyer played by Matthew McConaughey, then fade from view.

More importantly, I was constantly distracted by the film’s whitewashed esthetic. The details are all wrong. The Amistad prisoners all seem ethnically African, yet every one smiles with a perfect set of shining white teeth. Moreover, Djimon Hounsou’s Cinque sports a muscle-bound 90’s physique which he somehow maintains through his malnourishment onboard the Amistad and the following three years of imprisonment. The African women wear demure tunics (which every 13-year-old reader of National Geographic knows to be inaccurate) until the inhumane slavers reduce them to nakedness. The film doesn’t fare much better with pre-Civil War America. Much of the film is set in New Haven (and was shot in Newport, Rhode Island) and it takes the viewer on the standard tour past brick buildings and church spires and singing Abolitionists.

While Americans North of the Mason-Dixon opposed slavery, society continued to be deeply rascist. The film declines to show us anything so complex; that might confuse Spielberg’s planned catharsis. We’re supposed to be moved and angered and ultimately, cleansed. Unfortunately, there isn’t anything to feel cleansed of: the case turned out adequately, but slavery continued in the South for another 20 years and the freed prisoners from the Amistad didn’t meet with a happy ending.

The performances are mostly flat, with a few exceptions. Anthony Hopkins, who seems to be making a career out of playing US presidents with strange accents, wears so much luminscent pink eye makeup in one scene that he implies John Quincy Adams was not only a founding father but also a founding drag queen. McConaughey manages not to embarrass himself, and Hounsou deserved the Golden Globe nomination he earned as Cinque. Every other character is so steeped in cliché that each seems to have his plot purpose stamped on his forehead. It’s hard to blame the actors (except Hopkins): only McConaughey and Hounsou were given any kind of character to work with.

Spielberg’s greatest sin, however, lies in the movie’s ending. We hear the verdict read and see the triumphant bombing of an African slave fortress as Cinque and his men sail home across a sunlit blue ocean. It is only in a small caption printed beneath Cinque’s smile that we learn that he returned to a land riven with civil war, never to see his wife and children again. They had either been killed or sold into the slave trade themselves. The language of the movies is visual and Spielberg knows it; here, he displays a comforting image even as he acknowledges the horrific reality. Somehow, he wanted to convince us that everything turns out all right in the end, even when it doesn’t.

A copy of 'Amistad' can be purchased at BuyIndies.com.