See, Spot, Run: Working with Composers, part 2 of 3

Written by Scotty Vercoe | Posted by: NewEnglandFilm.com

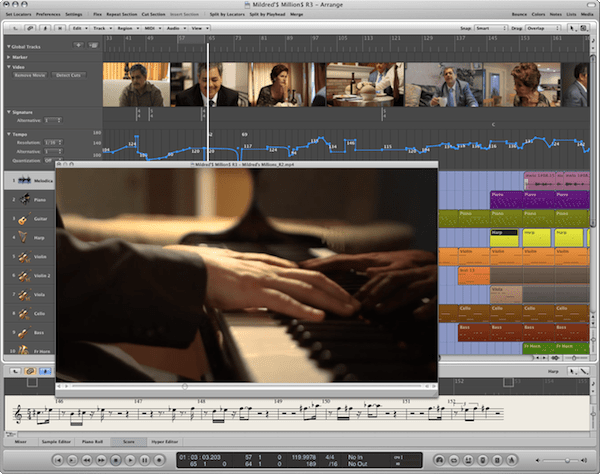

Some of you may be asking: what is a spotting session? The spotting session is when a director and a composer watch the film together and decide when the music cues will start and stop, as well as the general mood and trajectory of each cue. The film’s producer, music editor, and music supervisor may also be present, but the main participants are the director and the composer. Ideally, the composer has already watched the film and is not seeing it for the first time at the spotting session. Through meaningful discussion and detailed note-taking, the goal of the spotting session is to give the composer everything he or she needs to start scoring the film.

Spotting Session Goals

Before beginning the spotting session, both the director and the composer should first think in broad strokes about the role that music should play within the film. This raises a few questions.

What is the goal of the music?

Spotting a film demands careful consideration of the film’s genre, narrative arc, and editing rhythm to inform a composer’s music choices. The music’s genre and general mood should make sense as they relate to the narrative.

How much music is there?

In the early days of film, composers often had “wall-to-wall” music, meaning that virtually every scene in the film had musical accompaniment. While this practice has long been abandoned, it is important to note that even the amount of music in a film can be influenced by the film’s genre. As John Cage boldly illustrated in his controversial piece 4’33”, silence can be one of the most powerful elements of music. To convey a stark sense of realism, some films have no music at all (The Birds, Castaway) or very little music (No Country for Old Men).

Where does music come from?

Even without underscoring, a film can cleverly employ suitable music. For instance, all the music heard in the film Rear Window comes from on-screen sources like radios and musical instruments (also known as diegetic music).

What scenes have music?

Finding the optimal time a music cue should start and end is highly subjective, but there are some guidelines that can help composers and directors work through the issue. A music cue’s entry and exit times often line up directly with the beginning and end of a scene. To smooth over on-screen transitions, music (as well as audio and/or dialogue) sometimes starts just before an edit point between scenes. These few seconds of sonic foreshadowing can prepare the audience for the next scene. Just as often, a music cue will start on an emotional beat. An emotional beat can be romantic as well as dramatic. For example, in Chinatown, as Evelyn is tending to Jake’s wounds, Jerry Goldsmith’s romantic music enters as Jake gazes deep into her eyes before they kiss. Whether in conjunction with scene edits or emotional beats, a music cue’s entry and exit points should be carefully chosen to suit the narrative.

Are there moments the music should hit?

In almost any production, there are significant moments that practically beg for musical punctuation. A classic film noir example is, at the moment the identity of the killer is revealed, the music suddenly enters with a dramatic, dah-dah-dunn (Shock Horror by Dick Walter). This type of music cue is so iconic, it is now often spoofed in comedies and cartoons like The Simpsons. A similar type of cue is commonly referred to as a stinger, which is a sudden impact on screen that is mimicked in the score. In Hitchcock’s Vertigo, at the exact moment that Madeline ‘falls’ into the water, Bernard Herrmann’s music reacts instantly to the action with a powerful stinger. Stingers can also be less dramatic, for instance, in Gone with the Wind, when Scarlett throws a vase in frustration, Max Steiner’s music follows the vase with an almost light-hearted stinger as it shatters.

Remote Spotting Sessions

Although the ultimate goal remains the same, spotting sessions need not happen in person. In today’s hyper-connected world, people are finding it easier and easier to collaborate remotely. Spotting remotely does, however, introduce a set of challenges and pitfalls. With remote collaboration, the easiest trap to fall into is miscommunication. I once began a project that fell into miscommunication almost immediately. I spoke with the director by phone, and then I received a cut of the film. Wanting to get a head start while I had a free day, I began to sketch out some ideas for the score. I informed the director that I was sending him a piano-only draft, and that I would both develop and orchestrate the ideas. Instead of lining up the soundtrack to the film and giving me measured feedback, he responded that he wasn’t feeling this “tune” and inquired if I had anything else. I neglected to notice that what he had sent me was not a final cut, so all the work I did to line up music with the drama had been for naught. It is no stretch of the imagination to think that this would not have happened had there been a face-to-face spotting session. But I also believe that the miscommunication could have been easily avoided had we simply done a remote spotting session, either by phone or video conference.

Here are some tips for directors and composers to help maximize the effectiveness of spotting sessions.

DO

- Watch the film before attending the spotting session.

- Think about the role music should play, as though the music were a character.

- Consider the arc of the narrative, not just the scene in question.

- Discuss the overall style and instrumentation, but only in very general terms.

- Take detailed notes on each music cue’s timing, mood and style.

- Composers: Try to understand the director’s vision and react accordingly. Once you grasp the director’s vision, be clear to the director about your goals for the music and what you can bring musically to the film.

- Directors: Be specific about any timing, emotional or stylistic ideas. Understand that film composers exist to enhance your vision of the film, but need guidance in terms of the directorial vision.

DON’T

- Get caught up in minutiae and/or overly specific musical details.

- skip or rush the spotting process!

- Composers: Don’t expect the director to know specific musical terminology, but instead be prepared to discuss music in layman’s terms (unless, of course, the director has a music background).

Scotty Vercoe is a film composer, jazz pianist, instrument designer, music emotion researcher, and educator. He has composed for independent films, the National Film Preservation Foundation and numerous 48 Hour Film Project shorts, winning two Best Musical Score awards. For more information see: http://scottyvercoe.com

Related Article: Shivers from Timbres: Building Emotional Soundtracks, part 1 of 3

Scotty Vercoe is a film composer, jazz pianist, instrument designer, music emotion researcher, and educator. He has composed for independent films, the National Film Preservation Foundation and numerous 48 Hour Film Project shorts, winning two Best Musical Score awards. For more information see: http://scottyvercoe.com