Females in Film | Filmmaking | Interviews | Local Industry | New England

The Double Discrimination of Female Filmmakers

In her recent book Independent Female Filmmakers, NewEnglandFilm Founder Michele Meek says it's not just Hollywood who discriminates against filmmakers; it's all of us—film scholars, fans and curators.

Written by Suzy Cosgrove | Posted by: NewEnglandFilm.com

A conversation with Michele Meek on gender disparity in filmmaking and her latest book Independent Female Filmmakers: A Chronicle through Interviews, Profiles, and Manifestos, available on Routledge and Amazon.

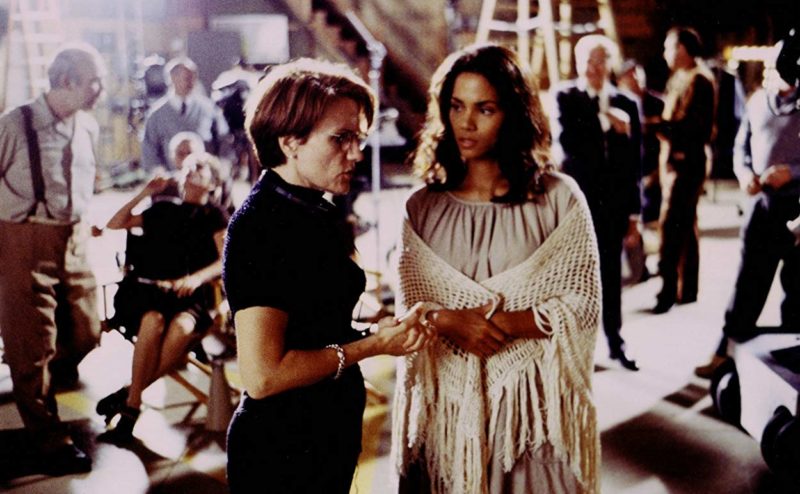

In Michele Meek’s latest book, Independent Female Filmmakers: A Chronicle through Interviews, Profiles, and Manifestos, she interviews filmmakers such as Ericka Beckman and Martha Coolidge (both with connections to the New England area) and takes a hard look at the varying levels of discrimination towards women in the filmmaking world.

Suzy Cosgrove: What inspired you to begin work on this collection?

Michele Meek: It started because I was part of The Independent when it re-launched as an online publication back in 2007. When the AIVF (Association of Independent Video and Filmmakers) went under, there was a call for organizations to take it over, so I helped form Independent Media Publications, and we launched it as a website. So I long realized the importance of the archives of the publication. From 1976 to 2006, The Independent was active in covering independent and grassroots filmmakers who weren’t necessarily getting coverage in other outlets. Once I took over the publication we started the process of organizing and digitizing these pieces and I figured since I wanted people to start using them, that I should start using them too!

At first I thought of it as a compilation of interviews with filmmakers from the past but of course we needed to include some contemporary filmmakers as well as the publishers were hesitant to publish a book of only interviews that had previously been published. But this presented a unique opportunity to show the continued relevance of the filmmakers’ work and gives the reader a sense of where the filmmakers were in their lives when they gave the interview, and where they are now.

SC: When did you start thinking about this book? I’m curious because of the political landscape now, in the US specifically. What was going on at the time you decided to make this compilation, and did it influence your creative decisions?

Meek: Well championing women’s work and achievements in filmmaking has been a long term interest of mine, so that was nothing new. I started this project years before the #MeToo movement or #TimesUp. I came to realize over time that there just weren’t enough books about women in filmmaking, and I wanted to create a compilation that profiled a number of important women filmmakers who truly all deserve a book of their own. There’s really no reason they shouldn’t each have their own book. So, this was a start in that direction, and a way of giving them a way to speak for themselves because it is mostly interviews and manifestos, most of the words are theirs, which was really important to me.

SC: How do you go about going through over 30 years worth of interviews to decide what to put in the book?

Meek: Well the first thing I needed to do was decide which filmmakers I wanted to have in the book, so that meant sifting through a lot of archives and finding every single woman filmmaker that was ever featured. Of course it’s not an objective process, so I would ask other people their opinions, and it was very difficult because I obviously couldn’t include everyone.

Once I had that list, I figured out which of the chapters I could handle myself, Jennifer Fox and Martha Coolidge, and then did a call for writers at different universities. I was looking mostly for academics who could interact with their work on a more scholarly level but it was interesting as a process because there were writers involved who were journalists, and also writers that were solely academics. It didn’t occur to me until I got through the process of compiling this book that interviewing a person is an acquired skill that takes time and practice to develop. It also didn’t occur to me how I might need to guide academics who were not comfortable or accustomed to speaking directly to filmmakers. In some cases, they were used to working directly with the filmmaker’s work as it was on the screen without them being part of it.

SC: Would you change how that process looks if you were to do a second version of this book? Would you assign a journalist/academic pair?

Meek: I think the dynamic of one-on-one interactions is the best for an interview. The common interests between two people spark connection and interesting conversation. I think next time, I would look for scholars who all also have journalistic experience. I also think, next time around, I would be better equipped to guide them. It all turned out great, but in some cases I would have to ask the writers to go back and interview the filmmaker again.

SC: So as I was reading the book I came across a parallel between the way in which you came to decide what this book would be compiled of and the way in which women decided the kinds of movies they made. Meaning there were outside influences, prejudices and general rules that made including current filmmakers a necessity much like the influences, prejudices and general rules that forced women into independent and experimental filmmaking because they were not able to participate in larger budget, studio funded, feature films. Can you speak a little to women filmmakers having to switch gears and pivot when they’re on a creative path to have their work be seen?

Meek: That is really one of the most important things that came out of this book, which is that women filmmakers experience discrimination at two points in their career. They experience discrimination first when they are getting their films made and funded which ends up driving them to explore web series, television, documentaries, etc. The second instance of discrimination is something I hadn’t really fully acknowledged or understood before I did this compilation, and occurs in how their work is seen and remembered. That is something that’s important for us in academia and journalism to remedy.

So the first problem is with Hollywood and the discrimination there, to which the solution would be to make it easier for women to get their work made. But the second problem is once the work is made. There are really important films by women, and why is this work not up there with the other male directors’ work? This is a level of discrimination I didn’t even realize was there before I worked on this book, and now it’s become so blatantly obvious to me.

The University of Mississippi Press has a series Conversations with Filmmakers, and out of the 108 interviews they’ve done, only seven of them are women. There’s truly no excuse for that, as there are hundreds of women filmmakers that would be relevant for that series. Academic books in general don’t make a lot of money, so it’s not about the books being hugely profitable. In that case, why choose 101 male filmmakers, and only seven female?

Something is wrong with the criteria if these are the numbers that you’re getting—something is fundamentally wrong in how these decisions are being made.

One of the reasons that women are not remembered in the same way that male directors are, is because their careers are often eclectic because they were discriminated against in the industry. So it’s not fair to not count the one or two great films that they’ve made just because it’s not part of a more robust body of films that all cohesively go together. That model needs to be totally uprooted if we want to actually make a change in the way we see film.

SC: Yes that’s another point that really struck me in the book—which is that if we don’t change the way we think about and see film, then the culture of filmmaking won’t change. On that note, are you thinking of a follow up to this book? I know you had mentioned in the intro that you had to omit a lot of people that you wish you could have included. Are you thinking of doing a Volume II?

Meek: I haven’t thought about that yet, since I’ve been doing a lot of promotion for this book, so my head’s been in the space of getting this book off the ground and to the place it deserves. Once that’s where I’d like it to be, then I can begin to think about what the next project will be.

I think if I do end up doing a second book of interviews, my focus would likely be European female filmmakers because The Independent profiled quite a few women who don’t—although they should—have their own books already. It could then also be a then-and-now collection as this current book is.

For more information about Michele Meek, visit her website at http://michelemeek.com