Deception. Dissection. A New Perception.

Written by Sara Faith Alterman | Posted by: Anonymous

It seems practical, even reasonable, to rely on news organizations to broadcast accurately. Such informational institutions exist to dig up the facts, right? Maybe not. In the aftermath of President Bush’s crusade to eliminate the seemingly omnipotent threat of ‘weapons of mass destruction,’ it has become pretty obvious that what initially appeared to be a deed of heroism and liberation was actually a vicious act of messy retribution. The burning question is, how much did the embedded American media uncover while reporting from the Middle East? Were American audiences actually getting the facts as they unfolded, or were we shielded from the truth?

Danny Schechter seems to be just the man to investigate suspicions about the media; he himself spent years entrenched in media production, and his experience is deeply rooted in the Boston area. A one-time Neiman Fellow at Harvard, Schechter has worked for Channel 2, Channel 5, Channel 56, and, most memorably, spent 12 years as the news director/"news dissector" at WBCN. He is currently the Executive Editor of MediaChannel.org.

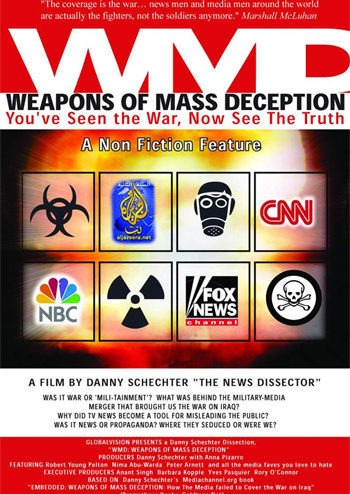

Schechter’s new documentary "WMD: Weapons of Mass Deception" asserts that Americans were cheated out of thorough coverage during the war on Iraq. Investigating the theory that audiences are at the mercy of a media with ulterior motives, the film explores the paradigm of fact versus ‘good television,’ and provides substantiation to those who have suspected all along that American audiences are hardly getting "the truth and nothing but."

SFA: What inspired the production of this film?

Schechter: In the course of my work as a journalist, I became conscious of the gap between what is reported often, and what is really going on. So I developed a clear awareness that a lot of our journalism is flawed, that we’re not getting the full story. When the Iraq war came along, I embedded myself in my living room and began watching. I wanted to compare what we were seeing as Americans, and what people in other countries were seeing, to the degree that I could. I watched the BBC and the CBC (Canada), and I saw there was a tremendous gap in coverage; those stations were reporting one war, American stations were reporting another. That led me to write a book, called Embedded; Weapons of Mass Deception. Since I’m also a filmmaker, I started out to make this movie. Doing it was very hard; first of all, no media companies wanted to fund a movie about themselves. Secondly, at the time I started, everyone’s attitude was "Gee, this coverage is great! There’s a war that’s happening right now, and we’re right on top of it!" I was one of few people who didn’t feel that the war coverage was very good.

I began to realize, when interviewing people, that there was a deeper story here, about how the war is being sold to the American people. I wanted to explore the roles that the media and the government were playing, often together. The whole war was premised on the idea that we were threatened by "weapons of mass destruction," and now, of course, we know that there were no such things, that our news was exaggerated and inaccurate. That’s why I called the film "Weapons of Mass Deception"; it was obviously a play on words. I think it captures the feeling that we were being lied to by the very institutions that we trusted to bring us the truth.

SFA: Do you see the American media as a mouthpiece for our government, or as being at the mercy of limited and controlled sources?

Schechter: Media companies have their own interests. They have an interest in getting ratings, getting an audience, making money. Many of them felt strongly that, in the post 9/11 environment, that [patriotism] was needed. They weren’t forced to tailor their broadcasts that way, but they bought into it nonetheless. But also they knew that war is a very good format for bringing in an audience. It’s exciting, people are at risk, nobody knows what’s going to happen, et cetera. As a consequence, a lot of people tune in to see the broadcasts, the "Showdown with Saddam."

One of the things I do with my film is make the suggestion that one of the reasons the networks went along with this [patriotic theme] so enthusiastically is that they have their own interest with the government; they wanted the FCC to pass these new rules that would allow big media companies to buy even more stations, and they were lobbying the FCC. The suggestion was made that if the FCC waives the rules, they [media companies] wave the flag. This is something that wasn’t even covered in our press, the idea that there would be a relationship between the war and the FCC.

We are now in the age of global broadcasting. American media is very powerful, so it helps frame the issues for the rest of the media; they tend to follow the American media lead in many cases. So in an age of multi-national media companies, like Time Warner, you have the idea that the nation state as the target of an audience is no longer accurate. To talk about the way in which the media shapes the way we understand things, in the case of the war, I felt there was a lot more selling than telling. In other words, an accepting of the inevitability of it [the war], but not challenging it! Not playing the role that journalists are supposed to play. So my film is about the media, but it’s really about our democracy, saying that democracy is being put at risk when we are not being informed by the people we trust to inform us.

SFA: Tell me about some of the characters in your film. Who did you interview?

Schechter: Actually, I’m one of the characters. The people managing the media side of the war were very secretive. They wouldn’t grant interviews, they wouldn’t provide access, they limited and controlled information. When reporters did speak to them, they all spoke from message points; they didn’t get very much from them, just the same reiteration of the same things. You know, "What day is today?" "Well, it’s Tuesday, and Saddam still has weapons of mass destruction." No matter what you asked, these people would come back at you with their pre-formulated message points. It was characteristic of what’s called ‘information warfare.’

One of the characters I interview in the film is Robert Pelton, an independent journalist who wrote a book called The World’s Most Dangerous Places. He ended up unable to go to Iraq, so he embedded himself with journalists. In the film, he tells me the stories about the journalist themselves, and how a lot of them were there for career reasons. Another person in my film is Sam Gardner, who is a retired Air Force Colonel, and he did a study, and claims that 50-60 stories of the war were distorted or exaggerated, if not invented, in order to hide the truth about what was happening. I also have a woman named Gwendolyn Cates, who was an embedded journalist for People magazine, and she gave us some inside information about what it was like to be embedded, and some footage that she shot.

There are a lot of different people in my film; the film is sort of an argument, it presents a point of view based on a lot of research and investigative journalism. It’s not a traditional kind of documentary; it offers my perspective. Since I’m known as "the news dissector," I’m dissecting the coverage as I go through it. I think that people will come away [from seeing the film] with a lot of information that they didn’t know. Not only about what was covered, but also about how it was covered and what was covered up.

SFA: Would you have been able to make the same film if you didn’t have so much prior experience in the media?

Schechter: I think the film is a wide-ranging look at the media system, and how the news ends up shaping our understanding of what’s going on, in an inaccurate way. Having worked in the media, I was much more aware of certain media techniques and tricks. I talk about what’s called ‘mili-tainment’, the way in which military conflict was presented with entertainment techniques, and I show them in the film. For example, the networks have their producers take the camera off the sticks, move it around, so you get a more vérité look, make it more exciting that way. I found a military memo, encouraging producers to use cameras that would enhance the excitements of the shots. The graphics, the music, the promos, all of it was about packaging.

SFA: Do you think that the average American viewer sitting in their living room, which is exactly what you did for your research, is aware that what they are watching on television may not be the full story, that what they’re seeing is cause for suspicion?

Schechter: I was just talking to someone from Russia. In Russia, it is common knowledge that the media is totally controlled, so nobody trusted it. In America, it appears that the media is totally uncontrolled, and everybody trusts it! Even though, in effect, it is controlled. So we have the impression that we’re getting [the truth] because the broadcasts look so authoritative; the anchorman goes to the embed who’s standing in Iraq, goes back to the expert general in the studio. We get five different people telling us the story, it seems so credible. But other voices are not heard! For example, the head of the BBC, and this is in the film, says that during the American coverage of the war, there were 800 experts interviewed on all of the American television networks, out of which only six were critical of the war. So other voices of people that may have been critical of the military weren’t heard at all.

What Michael Moore’s film "Fahrenheit 9/11" demonstrated is that there is a tremendous market for and interest in other voices and other points of view that we’re not getting through our mainstream media. There used to be a lot of independent distributors, but now most of them are controlled by big media companies. Getting distribution is difficult; when you make a film, usually in Hollywood, half of the money is for making it, half is for marketing it. But in independent film, 150 percent goes into making it! You’re immediately at a competitive disadvantage to get the film out there.

SFA: So where can people see your film? I understand you’ve already screened it at various festivals, especially in the New England area?

There are a lot of people in the Boston area who remember me from WBCN, so I’m sort of marching it around New England. I’ve shown the film the Nantucket Film Festival, I’ve shown it at Woods Hole, I showed it at the Boston Political Film Festival. I think Northampton wants it, I’ve been invited to show it in New Hampshire, the Coolidge Corner theatre would like to run it. I want people to see it! And I think there will be a lot more media interest in New England once I have it out there.

For more information about 'WMD: Weapons of Mass Deception,' including upcoming screenings, visit www.embeddedwmd.com.