Editing | Filmmaking | How To's

Shivers from Timbres: Building Emotional Soundtracks, part 1 of 3

Written by Scotty Vercoe | Posted by: NewEnglandFilm.com

Most of us have had the experience of listening to music and being moved so intensely that the hair on the back of our neck stands up. The “music chills” is just one of many very visceral reactions people can have to music. Music can evoke joy or sadness, rev us up, calm us down, turn us on, or creep us out. After watching The Omen, I remember having nightmares not necessarily from the film, but from Jerry Goldsmith’s spine-chilling score. While the music itself really is quite eerie, it was the immediate association with the film that enabled such a powerful effect. Hearing the music alone could trigger the same feelings I had experienced while watching the film. Moreover, just thinking about the ghostly choir parts was enough to put me right back within the film’s unsettling narrative.

Categories of Emotion

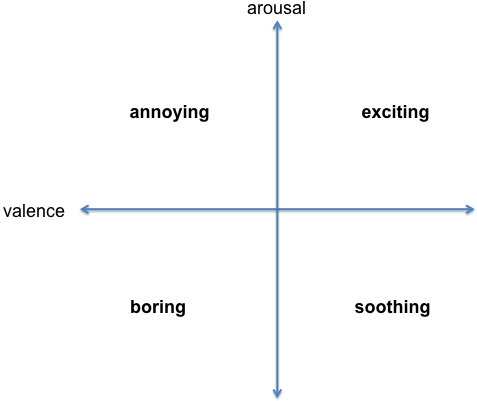

Psychologists often use broad categories of emotions to enable their research. Psychologist Dr. Paul Ekman proposed six basic feelings of happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust and surprise, while Dr. Robert Plutchik used positive and negative pairs of feelings: joy/sadness, anger/fear, trust/disgust, surprise/anticipation. Other researchers plot emotions in 2D space using dimensions of valence (how positive or negative the feeling is) and arousal (the extent or level of the feeling). Filmmakers can view the evolution of their story and visuals along these angles to help jump-start the process of thinking what emotion should arise from the music.

Music-emotion scholars also use these categories to facilitate their work, and, in addition, trace ways that music conveys emotion. In the 1930’s, researcher Kate Hevner played short music examples for her subjects and asked them to describe the emotions conveyed in what they heard. Each music clip in her experiments had slight adjustments in a single element of the piece, such as tempo or dynamics. She found eight general groups of adjectives people used to describe emotions, representing serious, sad, dreamy, soothing, playful, happy, exciting and majestic feelings. She also discovered predictable emotional changes when a musical feature was shifted. For instance, speeding up a piece of music makes it more likely to be happy or exciting, while slowing it down likely makes it more serious or sad. It has also been shown that generally, changes in musical features are culturally universal. Even a remote jungle tribesman free from Western musical influence will perceive faster music as happier or more exciting.

Music and Emotion

First described by theorist Leonard Meyer, music emotion is often a result of creating an expectation and veering from what the listener anticipates. Longer musical phrases often consist of a series of shorter sequenced patterns, many times just two or three notes. Each repetition builds a certain expectation in the mind of the listener. Emotional reactions occur by “tricking” the listener to expect a continuation of the pattern, and then turning the phrase unexpectedly. The proportions at which patterns and changes occur may vary greatly, but in essence have remained similar across centuries of music history and spanning many cultures. For instance, a Bach fugue from the 1700s might build expectiation and release very quickly within each musical phrase, whereas a minimalist Philip Glass score from the 1980s may develop expectations for a few minutes before surprising the listener. Suspending a listener’s expectations can happen in a purely rhythmic context, like the syncopation of an Indian tabla performance. Regardless of domain or culture, hearing the unexpected is a cornerstone of musical expression.

In film, music is often used to convey emotion that supports and propels the narrative. Traditionally, emotions on screen have the same general emotion as the musical score. Moments are accented throughout, such as a love scene with sweeping romantic music that swells as the lovers embrace. In this case, the emotions of the film and the music are identical, simultaneous and intentionally obvious to the audience. Just as often, music can single-handedly set the correct tone of a scene. For instance, in a horror film we might hear creepy, sparse percussion as a group of teenagers arrive at a remote cabin. Nothing on screen is scary, but the music will start to build the tension.

The chronology between emotions on screen and those implied by the music can also be adjusted for effect. Music emotion can be synchronized with the action, used to reflect on the past or foreshadow future events. When placed before a significant event, music can warn the audience, such as eerie music preceding an attack. Music can also act as emotional punctuation immediately following an event. In North By Northwest, Bernard Herrmann’s music enters only after Jimmy Stewart’s character causes the assassin’s plane to crash. Here, the music is a reflection of how adrenaline can help postpone crippling fear until after the danger has passed. Clearly though, most soundtracks involve some combination of emotional timing between screen and score.

Occasionally, the emotion of the music is at total odds with the visuals. While sometimes used for ironic humor, generally, the technique of using music that “runs counter to the action” is designed to make the audience think more deeply about and explore the possible interpretations of the images shown on screen. When the image doesn’t match the music, it lures the viewer into a more meaningful interaction by jarring their expectations. In A Clockwork Orange, the contrasting moods of violence and the song “Singin’ in the Rain” make the scene all the more shocking. In Good Morning Vietnam, the irony of Louis Armstrong’s “What a Wonderful World” makes the scenes of violence and destruction feel even more poignant.

Music and Associations

While not strictly operating on an emotional level, music often conjures ideas based on past associations. The sound of monks chanting may evoke the image of a monastery, just as the sound of a shakuhachi might suggest Japan. Situational music — wedding processionals, funeral marches, “Taps” and the like — can bring to mind specific concepts and related feelings. Sometimes music is chosen for reasons of historical significance. When HAL is being dismantled and regresses to singing “Daisy” at the conclusion of 2001: A Space Odyssey, it is a reference to the first melody ever sung by a computer, synthesized in 1961 by John Kelly and Max Mathews. Even though associations like these may be recognized by audiences, by nature they start to become less culturally universal.

Rather than relying on known themes, intense musical associations can be developed instead. Who can forget John Williams’ iconic theme for Jaws? The now-classic two-note motif quickly became synonymous with the shark’s imminent approach. Attaching a theme to a character harkens back to the idea of leitmotif used by Richard Wagner in his operas. The first widespread appearance in film is Korngold’s masterful 1938 score for Robin Hood, in which each of a dozen or more characters (Robin Hood, Will Scarlet, etc.) and concepts (such as oppression) has their own theme. More recently, Howard Shore’s soundtracks for the Lord of the Rings films make extensive use of character-based themes. Because their associations are created from scratch, leitmotifs are a useful tool for establishing emotion and meaning in film music.

As you listen to a film’s soundtrack, as a filmmaker or audience member, consider the musical thought process:

– How does the emotion progress throughout the story?

– Is the music always in emotional and chronological alignment?

– Are there musical motifs based on characters or ideas?

– Is there associative music that assumes cultural knowledge?

Whether using music that supports or contrasts, precedes or follows, builds associations or sets a mood, examining the emotional arc of a story can help us develop a plan for building an effective soundtrack.

Scotty Vercoe is a film composer, jazz pianist, instrument designer, music emotion researcher, and educator. He has composed for independent films, the National Film Preservation Foundation and numerous 48 Hour Film Project shorts, winning two Best Musical Score awards. For more information see: http://scottyvercoe.com

Scotty Vercoe is a film composer, jazz pianist, instrument designer, music emotion researcher, and educator. He has composed for independent films, the National Film Preservation Foundation and numerous 48 Hour Film Project shorts, winning two Best Musical Score awards. For more information see: http://scottyvercoe.com