Acting | How to Be a... | How To's

Raise Your Hand if You Want to Direct

Written by Raúl daSilva | Posted by: erin

Giving a guest lecture at New York University some years ago, I stood before a class of 62 people and posited the question, “Who among you wants to begin their film careers as directors?” Sixty people raised their hands. The two that did not raise their hands drew my interest. Upon asking them what they had planned, one said that he wanted to edit films and the other said that he planned on becoming a screenwriter.

My next speech drew a few sighs. It was this: “These two men are the only ones that will probably accomplish what they want to do in the film industry. This is because they chose jobs that have accessibility. They might also become directors much like many who began in film working behind-the-scenes and learning the finer aspects of the craft of filmmaking. The rest of you have little to no chance of jumping into the industry as directors. This is not to say that it will not happen. Who knows? Some of you probably have access to family money. If you direct films out of film school your chances to fail are also great no matter that you began with a good budget and a degree tucked under your arm.”

The greatest film school problem I had encountered back then, a condition that is more than likely prevalent today, is that a good number of instructors are loaded with degrees but have little practical experience making films. For the most part these film “scholars” have no real-life experience so they cannot instruct students on the day-to-day practicality of filmmaking.

My next question was one that could be answered by not a single person out of the 62: “Who can tell me what it is that a director does? What is a director’s job?” Since no one raised their hands I asked, “Why do you want to be directors if you cannot even describe the job that you would be doing?”

That’s when I saw the class instructor Brane Živković, a musician and film score composer who at that time instructed film-scoring theory, shift a bit in his chair. I softened the tone of my lecture.

So how is a good director made? Rather than reading my notions in this brief article, the answer will come if you go to www.imdb.com and look up the backgrounds of directors that you admire. They come from almost any field such as writing, editing, photography, the art department, and even choreography, as did Bob Fosse. The idea is that they mastered a more accessible craft before attempting to direct a film. A director is neither a “traffic cop” as we have heard from some glib directors being interviewed in the media, nor is she or he purely a person who realizes or visualizes a screenplay.

The consummate director is a visionary and visualizer, a person who pays meticulous attention to detail while conducting the interpretation of the written play along with actors and crew. The best of directors have been gaffers, best boys, even greens persons or insect wranglers. Not all actors can direct so it’s obvious that not all craftspeople can move up to directing. I can think of only one that has been truly successful — Clint Eastwood. Those who know his background (beyond acting) can easily explain why. (Clint studied directing under a master, Don Siegel, and he directs like Frank Capra who was a graduate engineer. He is known for his efficiency and his masterful control of the narrative.)

Other actors, such as Robert Redford and Warren Beatty, for example, who have won Oscars for films they directed, are in my humble opinion not successful as directors. The successful actor-director is not just the actor-director who wins festival prizes but who repeatedly draws audiences to their pictures, thus earning money for their employers, and being sought by the studios for more product.

The successful director is as the word says, “consummate.” Used as an adjective, not a verb, it means: “being of the highest or most extreme degree of performance.” Most of us cannot achieve perfection but all of us can aim in that direction. Directors who fail are usually not up to the job. They fail at different levels beyond not having the ability to select a good script or property; to know the craft of storytelling is almost a guarantee of success as a director; another detail and perhaps the best of them all. Others who fail are unskilled and/or lack vision. Many of these people are not the best arbiters of their own inabilities. They are driven by ego not the love of the craft. The lack of love of craft always shows. A business-like churning of a film by a dilettante director is usually flat and boring, often laughable, specifically in areas where humor was not the objective.

For example, at this writing, I can look back at some retro feature films and recall the lack of mastery in some of the most critical areas such as accuracy of period depiction. Not long ago I saw a few films placed in the WWII era but filmed within the last decade. This era is of particular interest to me so I believe that I know as much about it (the war and the military as well as what was taking place back “home”) as someone who actually lived in that time. Beyond that one of my friends who also worked as my cinematographer several times was a decorated combat cameraman who traveled with various units from Italy up to Paris, through Berlin and beyond to Berchtesgaden or Hitler’s mountain retreat also known as The Eagle’s Nest.

Uniforms in these films were wrong. The rank devices were incorrectly placed; caps were worn on the backs of heads while men saluted senior officers. The chances of these errors taking place in concurrent time are very small due to awareness and familiarity factors of the period. Even large budget films are often riddled with these errors. Cultural manners and vernacular are often greatly exaggerated in the decades following historically significant periods.

One film set in the 1940s showed a group of young men wearing T-shirts where a pack of cigarettes was rolled into the short sleeve and thus carried. Each character had done this where in reality this was a rare habit of the period. It was also unusual for men to place a cigarette in the ear and carry it that way, much less every man, as it was to show a room where every single person smoked. It behooves directors to source their depictions adequately, retro or not. Even fiction has rules.

But props are inconsequential compared to cultural and behavioral accuracy. Sometimes the director is ‘prop-obsessed’ for no reason at all. James Cameron insisted on going to the original manufacturers of the carpets on the Titanic and reputedly had exact carpets made for several million dollars — carpets that of course no one in the movie’s audience ever saw. Here’s a .

Recently in the often well-written, prizewinning television series, Mad Men, they showed the lead character at a picnic with his wife. When they rose to leave, they dumped all of their garbage on the grass and left. The lead — a Madison Avenue ad executive — even threw an empty beer can into the woods. Since I was not only fully adult during this period but had actually begun my work in an ad agency and before long had experienced work at three ad agencies and a large film studio, I clearly recall that no one at even my first ad agency would or could behave like a grunt, especially the creative director, which is the job of that leading character. In another show of this series the same character insults a client because she is an assertive woman.

In reality, anyone who behaved that way, even the creative director, would have been thrown out into the street by his supervisor. While it’s accurate that women were then not considered equal (a condition that unfortunately still exists even today if at a lesser degree) when it came to a female clients all such cultural ineptitudes ceased to exist and prompted me to write to the producers: “Any AE making the mistake of insulting a female client would have had his ass thrown out into the street. Even back then the client was a minor deity no matter the gender.

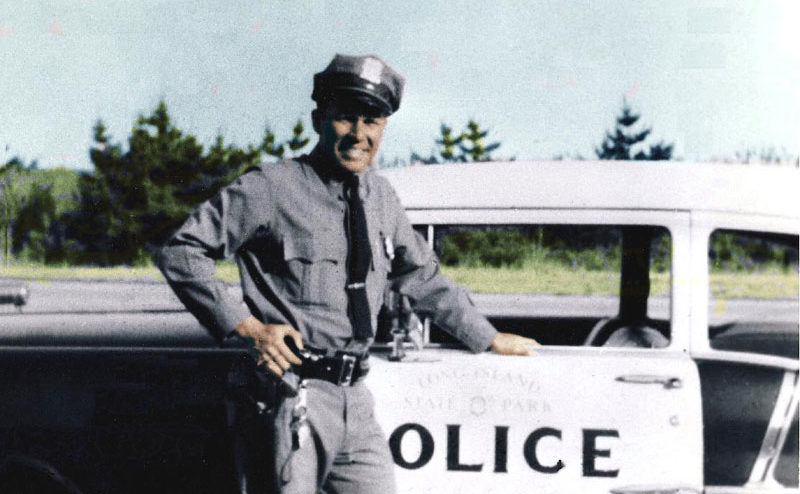

In another recent television show, Life on Mars, where the lead character, a police detective finds himself thrown back to 1973, we once again see the exaggeration of events and habitual behavior. For example the character’s unit supervisor is a brutal and excessively violent police detective, something that was very rare in 1973 and more appropriate to the 1920s. (Since I was a NY State Trooper in the mid 1950s while studying at Adelphi University, I’m fairly familiar with the police of not only that decade but also those following. Brutality such as that which has been documented in Los Angeles and other large cities is more the exception than the rule.)

When you see a film by Ridley Scott, for example, you will never see blatant inaccuracy in the minutest detail. In the case of erroneous or an exaggerated take on manners and culture it’s truly puzzling in the case of Mad Men because the script thus far has been otherwise brilliant with an equally fine cast.

Some will consider all of this “nitpicking” but that’s the point being made here: The consummate director must be a “nitpicker,” not just someone who wants to be in charge.