My Country, My Country: Inside One Man’s War

Written by Nancy L. Babine | Posted by: Anonymous

Dr. Riyadh and his family, a wife and six children, live in Baghdad. Riyadh, a member of the minority Sunni party, is a candidate for a seat on the Baghdad Provincial Council. Vehemently opposed to the presence of US military and committed to establishing a democratic government, Riyadh grapples with the conflict between his conviction that it is one’s fundamental responsibility to vote and the position of the Sunni party, which advocates a boycott of the election.

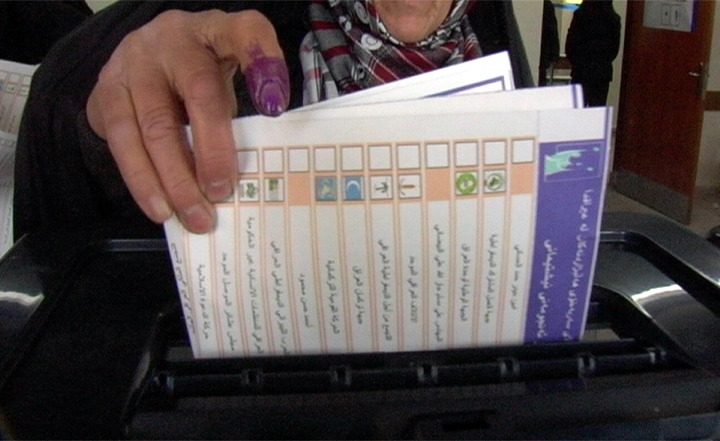

In his office at the Free Medical Clinic, he provides not only medical care, but encouragement, advice and a sympathetic ear. At home with his family, he cannot hide his anxiety over an uncertain future for his country and a growing despondence among his fellow Iraqis. The film expands beyond Riyadh’s story to reveal countrywide chaos and an impending threat of violence as election day draws near, including stunning scenes of Iraqis waiting in long voting lines while armed soldiers stand guard on the roofs of buildings.

The seed for My Country, My Country was planted when two women, merely acquaintances, discovered they shared a common interest in making a film about the war in Iraq. Glatzer and Poitras first met at the Los Angeles Film Festival where Glatzer was showing her film, The Flute Player (see NewEnglandFilm.com September 2001) and Poitras’s Flag Wars. They continued to cross paths on the festival circuit and began to consider the possibility of working together. When each was ready to move to a new project they decided to collaborate on a film about Iraq, though at that time they had no idea what the film’s focus would be. “We both felt that what was going on in Iraq was one of the biggest and most important stories of our lives,” Glatzer said. “And we had not seen anyone really capture in a long form film what life was like for regular Iraqi people living there during the occupation.”

Agreeing that the possibility of gaining access would be easier traveling solo, Poitras went to Iraq alone. Glatzer remained in her homebase of Boston to concentrate on raising funds, logistical matters and distribution. They spoke daily, and Poitras sent footage back to the US every week, allowing the filmmakers to evaluate how the story was taking shape.

“It became clear early on that the focus of the film would be the January 2005 elections,” Glatzer said. “That was all everyone seemed to be talking about in Baghdad when Laura arrived.” The team decided that Dr. Riyadh’s story would capture the essence of day-to-day life for an Iraqi living during this era of his country’s history.

Filming alone in a country at war confronted Poitras with enormous challenges on a daily basis: working in extreme heat, working out logistics of gaining access to meetings among both the Iraqis and the US military personnel, gaining the trust and friendship of people whose lives were under siege, and of course, the constant threat to her own physical well-being.

“I worried for Laura’s safety all the time,” Glatzer said. “And feared for the day I might have to take out our emergency procedure plan for a search and rescue.” For the filmmakers, the dangers that threatened Poitras only made the plight of the Iraqi people more poignant. During Glatzer’s telephone conversations with Poitras it was not unusual to hear mortar fire in the background. “Yes, it’s dangerous,” Poitras would say to Glatzer. “But there are 25 million people in this country besides me who are also in danger.”

Filmed in the observational style of cinéma vérité, Poitras attempted to document the drama as it evolved naturally while maintaining an unobtrusive presence. She seemed, according to Glatzer, to be in several places at once. Poitras filmed everything herself with the exception of election day. Due to travel restrictions imposed on Poitras and because the filmmakers wanted to authentically represent the dramatic events as the country voted, they chose to use additional cameras on that occasion.

As the producer, Glatzer faced her share of challenges stateside. Having worked with ITVS and PBS on past projects, Glatzer and Poitras had determined from the outset that they wanted the finished film to be broadcast on POV, the PBS showcase for independent nonfiction films. With a goal to create a film that would resonate for years into the future, Glatzer had to convince PBS that the film was not a news item that necessitated an immediate broadcast date. With her encouragement, PBS granted the filmmakers latitude in proceeding according to the time frame they felt best served the film.

A noteworthy triumph was engaging singer/songwriter Kadhum Al-Sahir for the original musical score. A top-selling singer in the Arab world, Al-Sahir was exiled from Iraq by Saddam Hussein in 1993. Poitras first heard his music while filming in the Riyadh home. She was so impressed that six months later when she was back in the US editing the film, she flew to Detroit where he was performing. She left a note and some footage backstage with his manager. Two days later they met and Al-Sahir signed on. His is the voice singing the plaintive Oh, My Country, a song he composed for the film. An ode to Iraq, the lyrics express the grief borne by the Iraqi people and the hope that one day there will be unity among all Iraqis.

The experience of making this film reinforced Glatzer’s belief in the consequence of acknowledging our common humanity. “Most of the Iraqis are kind, thoughtful, moderate people like Dr. Riyadh. When you see someone dancing or singing or laughing I think it becomes more difficult to hurt them.”

What does she hope an audience will take away from the film? “I think that all good films about war show that violence is counterproductive. For some reason humans need constant reminders of this.”

Glatzer continues to pursue projects that intrigue her. “There are so many people who live day-to-day in extremely challenging situations — and it is the stories of their lives that I am interested in telling. It is the individuals who have been pushed to their emotional limits without having a choice who have so much to say and so much to tell. Those are the stories I want to tell.”

Nancy L. Babine is a writer and filmmaker. She can be contacted at NLBab@comcast.net.

My Country, My Country was nominated for a 2007 Academy Award and a 2007 Independent Spirit Award. It aired last October on PBS and is being distributed by Zeitgeist Films. More information can be found at www.mycountrymycountry.com or www.pbs.org/pov/pov2006/mycountry. Nancy L. Babine is a writer and filmmaker. She can be contacted at NLBab@comcast.net.