A New View of Northern Ireland

Written by Ann Jackman | Posted by: Anonymous

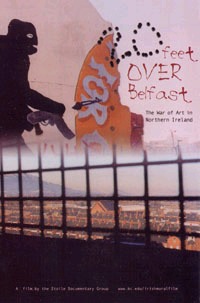

When someone mentions Northern Ireland, the first thing that comes to mind probably isn’t painting. And that’s exactly why Boston filmmaker, Paul Goudreau was drawn to the subject matter of his new short documentary, "20 Feet over Belfast," produced with Belfast-born Christine Hurson. The film documents the hundreds of brightly painted murals depicting Northern Ireland’s history, myths, and conflicts, and opens up audiences to a new way of looking at this area of the world.

After graduating from Boston College, Goudreau teamed up with his former film professor and mentor to produce a series of documentaries focusing on issues of social justice and reconciliation around the world. Through their company, Etoile Films, Goudreau has been able to satisfy both his filmmaking and travel bug, producing and shooting projects in Bosnia, South Africa, and the Middle East. Goudreau also freelances, and it was through one such assignment that he met Christine Hurson,, who has been living in the U.S. for the past 12 years. While they were both working on a project for Etoile in Northern Ireland, Goudreau was astounded by the quantity and beauty of the more than 300 Belfast murals, murals whose political symbolism had surrounded Hurson as she grew up.

In 1997, the two decided to produce a film on the murals, their artists, and their impact on the surrounding community. Shot on the side over the next few years while they worked on Etoile projects, "20 Feet Over Belfast" just premiered to good reception at the IFP Market in New York. By standing back and allowing both the art and the artists to speak for themselves, the 25-minute film quietly reveals a portrait of Northern Irish history and culture.

The murals adorn the walls of public housing and working class neighborhoods, and are painted by independent artists relying on donations of both money and supplies. At the height of the Conflict, they served as forms of heated political expression, and though that has mellowed somewhat today, they remain the source of an ongoing debate as to their aesthetic value. Are they art or graffiti? Do they celebrate Irish life or promote further violence? Goudreau and Hurson bring the viewers into this dialogue and ask them to draw their own conclusions.

Because the nature of the murals reflects the environment in which they are painted, Goudreau and Hurson’s film can’t help but touch on the issues surrounding Northern Ireland’s troubled history, but their film puts the focus more on art and creative expression and its continuing importance in a free society. While mindful of the past, it primarily celebrates the vibrant Irish present and its hopeful future.

AJ: Why did you want to make this particular film?

Goudreau: The whole theme reflected the kind of films that I’m interested in as a filmmaker. I like traveling and I like going to areas that people think they’ve heard everything about. So with Northern Ireland, people think they’ve heard all the stories. You turn on the news and you know you’re going to see some kind of paramilitary group or some kind of protests or bombs. We didn’t want to mention any of that. We didn’t want to talk about the rehashed political scene that we’ve been seeing over the years. But the painting. That’s new.

Hurson: Especially painting in Northern Ireland, because it always rains in Ireland. You don’t think, "Oh, murals, let’s go to Northern Ireland." That’s why I wanted to do the film, because I’d seen too many documentaries that just focused on the conflict and essentially tried to explain the unexplainable. And of course it’s a big part of Northern Irish life, but it hasn’t been everything. There’s a lot more going on there and I just wanted to say it’s not all doom and gloom. I really wanted it to have a positive tone that says, "Yes, we are moving forward. We have made progress."

Goudreau: I wanted to get the character’s life as a microcosm of what’s going on, without hitting the audience over the head with the same tales of woe. We wanted to let the art speak for itself and to actually create a fresh little look at what it’s like being a human being over in this part of the world.

AJ: What is the origin of the murals and what is their significance in Irish life?

Goudreau: They started around the turn of the century, but they mostly depicted Protestant heroes, celebrating William of Orange’s victory over Catholic King James in 1690. But it wasn’t until the troubles began in the 1960s that they began focusing on equal rights, and became more of a social campaign, like the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. That’s when the Catholics began painting too, and it became more of a dialogue and less of a monologue on one side.

Hurson: Early on, they were part of a celebration of Protestant history, but they were also very strong symbols of difference. They always had a lot more meaning.

Goudreau: Christine has very different opinions as a child growing up there. The murals have different connotations. As an American, when you first walk down the street and see three story high murals of glistening paint screaming out at you, you’re like, "Wow!"

Hurson: There’s definitely a wow factor. When you go to Belfast at the moment, there are a lot of tourists, many of them American. It’s funny that they’ve become a tourist attraction, because they always meant something different to me. The murals were indicators of areas not to go into and they were used to express political sentiments, because at the time there was a lot of censorship.

Goudreau: If a mural had too controversial of a message and it was just a little too close to the border, opposing sides would drive by and throw bottles of paint, sort of paint bombs to cover up the picture.

Hurson: And the other side would take that as a sign that the message was extremely effective because it got a reaction.

Goudreau: It was fighting without guns. There are still two guns, but they’re paint guns, I suppose.

Hurson: They’ve changed a lot in format though. Many of them are back to showing history and culture. I don’t think they have the impact that they once did at the height of the conflict. But they definitely are very powerful symbols of what people are thinking about. I read one writer who said, "The city uses its walls like a diary." And that’s essentially what this is — it’s like a diary of the city over the last 40 or 50 years.

AJ: Tell me about the artists.

Hurson: We focused on three muralists, and they all had very different personalities and very different reasons for wanting to do it. One artist considered himself a political activist. One dreamt of moving to New York and painting. Another used his murals as a message about boundaries. But mostly they wanted to get out and paint day in and day out.

Goudreau: And the thing that we liked the most was meeting the three guys. They’re great. They like to talk about their work just like any other artist. And they’re all just doing it for the art’s sake.

Hurson: Plus, Ireland is mainly known for its music and oral history or the written word, and this is something a bit new. A whole new way of expressing oneself.

Goudreau: There are over 300 murals, depending on how you count them. As many as 700 if you count the smaller pictures. One guy in the film says that there is no larger active mural painting community or public art scene anywhere in the world now that isn’t state-sponsored.

AJ: What was the reaction to your filming over there? Did you encounter any obstacles or resistance?

Goudreau: There’s something different about being an American and shooting there. You sort of go where you want. If someone stops you, when they hear your accent, they’re like, "Oh, OK, go about your business." But we were filming in some neighborhoods that Christine had never been in because as a kid, it was too dangerous to go into them.

Hurson: I knew exactly by the murals what area I was entering into, and immediately all the history of that area unfolds in your head. So I wasn’t really comfortable going into some of them alone, even in daylight.

Goudreau: But it was fine. They would ask around, the paramilitary groups, and they’d ask about us and I guess we’d been okayed.

AJ: How are the murals viewed within the Belfast community?

Hurson: When we were trying to decide how we wanted to approach the film, one of the things we were interested in was whether or not we consider the murals to be art or are they just graffiti. I’ve always felt that definitely they are art, because they have such a strong emotional impact. You can feel the emotion behind them in the colors and styles. But the community is split 50/50.

Goudreau: We present some of the opposing sides, some from the art community itself that say it’s not proper art, even if the artists are trained. A lot of people in the community don’t think they’re art, but they don’t feel they can say anything about it. One woman in the film says that even though she has asked them to be painted over, she can’t imagine who would go up on a ladder and do that, because she can’t imagine that person would actually come down alive.

AJ: What was the reaction to the film at the IFP market?

Goudreau: That was the first showing down there, and it was good.

Hurson: I think the IFP’s a really good testing ground. People laughed in the places they were meant to laugh. Because we didn’t want the film to be really heavy.

Goudreau: It was good to get feedback.

AJ: How would you characterize the style of the film and the choices you made in terms of shooting and editing?

Goudreau: We shot it on video. When we were over there filming other projects, we’d sneak away and get a couple interviews done on Beta. Then we went back and did a lot of stuff on DV. And there’s something to be said for having a smaller portable camera to climb up on scaffolding and for not attracting big crowds. A bigger camera creates bigger problems. And we were very pleased with the way it looked when we showed it at the [IFP Market].

Hurson: It really isn’t a traditional documentary style.

Goudreau: There’s one line of narration and then we just let the guys tell their own story. We specifically left out the artists’ last names until the very end, because in Northern Ireland, if you know somebody’s last name, you immediately know Catholic or Protestant. There’s no Irish music as well. Everything is straight ahead rock and roll.

Hurson: We did not want to have any Irish music.

Goudreau: We didn’t want to make it political. We didn’t use Irish music. It’s the anti-Irish Irish movie.

AJ: What are your future plans for the film? Will it be screening around Boston?

Goudreau: Our goal is festivals for now and then we’ll try to get distribution, which sounds very businesslike, but we have bills to pay back. We’ll try to find the broadest audience and see how it fares. But we’re still at an early stage. We’re going to show it at Boston College in December, and it will be interesting to see what the students have to say. Actually, the filmmaking community in Boston has been very supportive of us. They’ve been very helpful in offering advice and suggestions about festivals.

AJ: Have you shown it in Ireland yet?

Goudreau: We want to try and show it in Europe first and foremost, and then get it to come back to Ireland. They live and breathe the murals every day, so it’s not such a new thing for them. We want to try to show it to the rest of Europe, which is interested in European stories. Again, it gives them a different look at a problematic place.

AJ: Do you think there’s a future for short documentaries, in terms of audience appeal and funding?

Hurson: The short format is interesting to work in. Trying to do something in 25 minutes, you have to edit like crazy and really know what your message is.

Goudreau: The only negative, unfortunately, is that some distributors look at them as on a different level from feature length documentaries. It’s a good calling card for getting into festivals, but it’s not considered as serious as a feature film. It would be really nice if they’d show a short before feature films here in the U.S,, like they used to do in the 1950s. The other distribution angle is the Internet. The problem with the Internet though — it’s great, you get to see a lot of films online, but the problem is, they’re online! "Great, I can watch it on my little monitor and it looks crappy." But I guess it’s better than not seeing it. Will that change? I don’t know.

Hurson: I like shorts because they give you a little pause for thought. And I like to think that maybe that’s what our film does. It just stops people and gets them to thinking about Northern Ireland in a different way and encourages them to go there and see it for themselves.

Goudreau: It’s not going to cure cancer, but it’s a nice little look at an area that you think you already know.

For more information about the film, visit www.bc.edu/irishmuralfilm or email overbelfast@yahoo.com.