A Sorceress at Work

Written by Chris Donner | Posted by: Anonymous

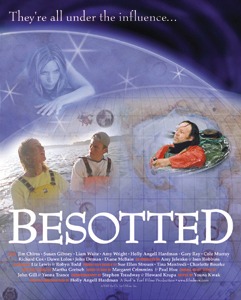

Writer/director Holly Angell Hardman is currently screening "Besotted," her first feature, and her first 35mm film. On screen, she also plays a sorceress cum matchmaker who manipulates the lives and loves of a handful of characters in a small New England town.

"Besotted" is a modern love story, as Hardman’s alter ego and her two accomplices cynically proclaim. More to the point, it’s a story about power, manipulation, and the tragedy that can result.

Hardman’s love interest, Shep (Jim Chiros), is a slovenly but likable local who drinks and pines after Vicky (Susan Gibbney), an independent woman who captains her own fishing boat and has a tough time dealing with people. Enter Damien (Liam Waite), a handsome Harvard boy looking for a summer job.

Hardman’s sorceress has plenty to work with. She eagerly pushes the characters around like pieces on a board, seeking the best for them…except when she’s feeling mischievous.

Off screen, I had a chance to talk with Hardman about a different form of sorcery — the process of making "Besotted."

Chris Donner: "Besotted" takes liberties with traditional narrative structure. I’m curious about how this might have affected editing the film. Did you feel more of a sense of collaboration with the video editor?

Hardman: Oh, god, yes. Certain editing rules apply if the story is just going to flow, simply to make it easier to watch. When you choose to make a film in a non-traditional fashion, you know that you’re not making it as easy for an audience. But so often I hear audiences saying that they do want to be challenged. And I’ve always been fascinated by surrealism, by any kind of art form that plays with bland reality. In my opinion, that’s how our minds work anyway. We’re always in different places: in our minds, in dreams, within our shared perception, in a non-human universe infused with some sort of perception beyond what we can grasp. I tried to convey some of that in the film — our smallness in the universe — particularly in the last shot.

CD: Would you say that, even while editing, you were still making narrative decisions?

Hardman: The question of whether we can control our own fate, and how dangerous is it to force reality — that element was already in the story from the very beginning. It was there with a simpler story, a story that was more one, two, three. I was always playing with the parallel realities, lives, but not throwing caution to the wind like we did eventually.

CD: So what happened to redirect you? To redirect the film?

Hardman: When we finished shooting on Cape Cod, we were sure we would finish the simpler story as I had originally planned. Then I was looking at the footage, watching Jim Chiros’ performance, thinking, "Oh my god, I know how I want to finish this film now." Even on the set, the day that Jim Chiros first came to work, afterwards everybody was like "This actor — who is he? He’s amazing." Just the subtlety, the detail. So a seed was planted. And it was not the original intent.

Back in New York, I would talk with different people who were involved, and I’d ask what appealed to them. Over and over again it was "That actor Jim Chiros. Shep. Shep…I want to know more about Shep." And I did too! Jim came in and he opened the door to a character I had created. He gave that character a life I hadn’t imagined. Plus, people were asking, "Do you really want to abandon what you’ve done in the past, where you played with a style of filmmaking that allows people’s minds to open up a little more?" Obviously, this is very much about the process — just even about how a film is made. So that was exciting.

CD: This is your first feature film. How was it different from making a short?

Hardman: (singsong voice) "Everybody warned me…" (laughs) It’s the same thing, except the night-and-day difference is the stakes. All of sudden people make it too important. I mean, of course it’s important — there’s a lot of money involved, blah blah blah. But doing a feature as opposed to doing a short — sometimes I’m tempted to go back to short films because it’s a friendlier world.

CD: When you say people make it too important, do you mean the money behind it, or do you mean the crew?

Hardman: The process…the crew. There’s less of a sense of sharing. You know, like "I’ll gaff on your film while you’re directing, and then this person can do costumes and we’ll work on her film." It’s more of a collaborative world going on there. I thought with my experience with short films that I kind of knew what it was like to be the director on set and the writer and producer and all this stuff. But you know that book "All I Want To Do Is Direct"? That’s pretty scary. You’re working with too many people who want to see you fail because all they want to do is direct. The attitude is that they’re there doing you — silly fool — a big favor by working on your film. I found that this did not continue when I changed crews. I realized I needed to work with a crew who had a better attitude. Usually it happens with your first feature, more often with women than men, to tell the truth.

CD: You mean women being the directors, not in the crew?

Hardman: Oh no, not in the crews. But it’s amazing how many have just decided it wasn’t worth it the second time around. I hope that changes. My experience was better — because we were doing this on location, and I had that break in between to decide if I was going to finish the way we started it on Cape Cod. I had this opportunity to rethink where I really wanted to go. I had been inspired to do other things — I think better things, although not necessarily more commercial things — that when a new line producer came in we just decided not to work with the same people from the first crew.

CD: There was no one left from that first crew?

Hardman: Well, Amy Jelenko had been on Cape Cod and she became one of the co-producers. Certainly a few remained. But I really ran into that first-time feature, woman-filmmaker, woman-director thing. A whole group of people willing to undermine the project, not having faith. Everybody saying: "You have no vision whatsoever. You have no idea what you’re doing." But I did have a vision (laughs). It was always there. And I also do a lot of yoga, so…between the two. Having a vision and doing yoga.

CD: Having a vision and doing yoga — now that sounds like a book title. So how many crews did you use? You said you worked with three DPs — was that three complete crews?

Hardman: Yeah. The DP, Howard Krupa, replaced a guy who had started on Cape Cod — I don’t want to mention his name because it was really unfortunate. I wanted the best. He had not shot on 35mm film before, and if you don’t have that kind of experience you better have a good attitude, or you better know what you’re doing. It was just a funny situation. Another thing that I would definitely advise people not to do — I thought, "Oh, the filmmaking world has really grown in New York. Why don’t I work with people I don’t necessarily know as well…or know at all?" This was naiveté on my part. I would have been better working as much as possible with people I knew, or who were recommended by people I know. I mean hey — everybody wants to do the right thing, right? I really believed that. Like a child – it’s not a very wise way to look at things, to think that everybody’s well intentioned.

CD: Plus, your crew is going to be larger on a feature like this.

Hardman: At first it wasn’t. That’s what I mean. I knew I had shot "Seaschell Beach" very much like a feature film. We almost decided to make it into a feature, it was going so well. So, as I say, I was more like opening up the door to a whole world of strangers that didn’t give a darn about what I was trying to do. It was just ridiculous. I waited to see the footage from the first DP and I saw things I couldn’t believe, like booms in the shot, he was always changing the framing…you know. There were other issues, but when I saw the footage, I knew we needed a change desperately. We shut down production for a few days, I talked to the DP who had shot my last film — Howard Krupa — he’s excellent. He came up and we finished what we could until it just got too chilly. We got what we could, knowing we didn’t really have the whole film because we had kind of lost two and a half weeks there in the beginning.

CD: This must have affected the story, and the actors as well.

Hardman: Well, there was the whole element of my watching the footage and feeling the Vicky character. It was there — her journey. We had it. Howard came and he was so involved in reshoots for the character of Vicky, getting the character right. I’ll give you a good example of something Howard did that was brilliant. You know that scene on the boat when she offers Damien the birthday cake and after that, she meets the really beautiful girlfriend? That was the Howard touch. And Susan just started experimenting. That was when I really started pushing her. I wanted to see colors. I didn’t want her just to be angry. I wanted this quirkiness, this woman who’s been away from society and doesn’t really know how to act with people if they’re not familiar to her, if they’re not fishermen. We wanted the feelings of what she’s encountered with growing older, the disappointments and insecurities. Susan really started loosening up her body and her voice, and Howard supported me in doing that. This is where we got our really special Vicky stuff. I mean, you love her.

CD: She can be angry, but there are moments when she just pulls you in and you wonder what this young kid is thinking. He’s got Ashley, who’s obviously attractive, but her personality is not at all developed. Vicky is so much more real.

Hardman: But Ashley will grow. Ashley’s young. I think that the Damien character really helps Vicky, but I don’t think…I mean, there’s a certain amount of condescension there. They don’t even connect sexually because he’s so caught up in his own vanity.

CD: I don’t think they’d be the perfect couple. On the other hand, this kid could probably learn a lot.

Hardman: In a Hollywood story, I think it could be forced. That was the other thing about forcing things. It’s like, no, that’s not really going to happen, but they can learn something from each other.

CD: So you worked with Howard…

Hardman: Then we continued in New York. He had a contract with another film and had to go back to LA. We felt kind of abandoned. So, when I thought of finishing up the film — which I needed to raise money for — we edited, and we said, "Okay, let’s just see exactly what we want and not do anything that isn’t planned." In the meantime, Stephen Treadway had been brought to my attention. Between Howard and Stephen, we’ve got a look for this film that’s extraordinary. Stephen and I met quite a bit before we began. We had every shot worked out, which is the ideal. So when we got to the set, everything just went like clockwork. On a 35mm film, we were getting 15 setups a day. As opposed to getting, with the first DP, maybe four or six. We just couldn’t finish the film like that.

CD: How did things go from there — working with the new DP and crew?

Hardman: Stephen brought in a crew that worked like a well-oiled machine. It was a set of saying "please" and "thank you" and smiling and jokes. We were getting 15 setups a day, but the crew was able to go swimming during lunch break. It was really like "Okay, yeah…I love making films." That was when we shot out on Long Island — North Fork. All the magical stuff.

CD: How many locations did you have? Just Cape Cod and Long Island?

Hardman: Listen to this — in the film, this is all taking place on Cape Cod, right? Well, we shot in different parts of Lower Cape Chatham, Orleans, East Harwich, Eastham, and then City Island, Staten Island, Park Slope, and Manhattan. One of the "Cape Cod" bars was right across the street from Penn Station. And then Southold on Long Island, North Fork. You wear out your welcome. You have to keep hopping.

CD: I’m curious about costs. Two questions. First, this was done on 35mm, but previous works were on video?

Hardman: No, my first film was 8mm video. Then I used 16mm black and white reversal, but I finished on beta. "Seaschell Beach" was done on 16mm. It was my first time doing 35mm, which mattered most in terms of budget. I was very glad I lived in New York, and that I had made contacts over the years without even realizing it — people who knew people who were interested. It wasn’t a lot of people. It’s still a very low budget. One financer backed out when I decided not to just do a traditional story, and then some exciting people came in after to help finish it up.

CD: That leads to the second part of the question. Did the style of the film and the narrative decisions you made affect financing and costs?

Hardman: With distributors, when I said I was making a film that didn’t have a traditional narrative form, Sony Classics was excited, Miramax was excited…I think they all just say they’re excited about anything (laughs). But we do have real interest now. I was speaking with the acquisitions person from Miramax who was first interested, and she actually took quite a shine to it, but out and out told me that without better known people, by the time they could make us known, they’d never be about to recoup what they’d put into it. That’s the market. I think the timing is good with this film right now to at least get…it’s done well with these museum screenings, and I think that with all that’s happening on cable, programming is opening up. Not in theaters — that’s shutting down. You see all these major distributors even at the smallest theaters now.

CD: I would think that a film like "Memento" would help…a film that uses an unusual narrative style and that has done well.

Hardman: Yeah, that was just made so well. That was so good. But then again, that was in the pipeline before and it did have well known people. That’s the way to make a feature film. I mean that is a successful way to make a feature film and use imagination. One of the best films I saw in the past year, no doubt. There are still the films I aspire to make. Okay, this is a first feature. It’s got something to it, a lot of special things going on. But I can do better.

CD: So you see yourself doing more features in the future?

Hardman: Yeah, they haven’t killed me yet. It was such a good experience as we kept going. It just started out so abysmally, but we turned it around. We did manipulate things (laughs). With a keen eye, we manipulated things. Not like playing that game in the film, that’s for sure. We weren’t trying to play with power. And really, we did start looking for nice people. That became a criterion.

CD: Where do you see "Besotted" going?

Hardman: Well, I’m planning to take it to Cannes. Just yesterday I was talking to a sales agent — that’s really what I needed. I think we’ve missed the boat for true theatrical distribution. It’s being in the pipeline. Kind of knowing that you’re going to get into the right film festivals, that you have talent involved that’s going to pique people’s interest. I mean, if you don’t have distribution, at least have that. I took a chance with "Besotted," and it may be a good film, but it doesn’t have the sexiness of name talent to it. That doesn’t bother me, but it sure does seem to bother distributors and they’re not shy about saying it. With television now, and people enjoying so much more home entertainment and these larger screens…at first I was like, "No, no, my 35 millimeter film — it must be seen in the theater." I don’t feel that way anymore. I’m gonna get a bigger screen (laughs). The key, I’m hoping, will be the sales agent who will get it into some foreign markets. I know how to make a film, but I don’t know how to sell a film.

CD: What’s beyond "Besotted"?

Hardman: I’ve been getting a lot of people saying, "You can’t just walk away from filmmaking." This has opened the door to my being able to bring in new projects with people who are more interested in developing. I’m developing two films now, and both of them take place in small towns, so I don’t have to worry about being killed for not shooting in New York (laughs).

CD: One final question. Any area showings of "Besotted" planned?

Hardman: Mass MoCA (www.massmoca.org) on April 18, in North Adams, MA. I wish I could show it in Boston. That would be wonderful.

CD: Any final comments?

Hardman: I’m just so glad that I did it. Because it was about the process.

Holly Angell Hardman has made three short films, all of which have screened in a number of film festivals in the U.S. and Europe. 'Besotted' is her first feature film. For more information about the film, visit www.filmbrew.com.