Beyond Black and White

Written by Jared M. Gordon | Posted by: Anonymous

Former Improper Bostonian and Boston Herald film critic

Paul Sherman has been keeping busy. This month he releases

his

self-published Big Screen Boston: From Mystery Street to The

Departed and Beyond, an exhaustive compilation of 250

motion pictures shot in the city.

Sherman defines a Boston movie as any film that, “takes the

trouble to bring cast members to Boston to shoot action here.” His collection

includes recent favorites such as Martin Scorsese’s The Departed, Clint

Eastwood’s Mystic River, and Gus Van Sant’s Good Will Hunting as

well as oft-forgotten, under-the-radar gems such as Jan Egleson’s Billy in

the Lowlands, Peter Yates’s The Friends of Eddie Coyle, and Christine

Dall and Randall Conrad’s The Dozens.

While a Big Screen Boston reader will very likely

happen upon a long-overlooked film to go out and rent, Sherman hopes that a

strong grassroots spirit as well as the upkeep of state tax breaks will inspire

today’s filmmakers to make their own contributions to Boston’s independent

scene. The following is an interview with Mr. Sherman, exclusive to

NewEnglandFilm.com.

Jared M. Gordon: Why did you write Big Screen

Boston?

Paul Sherman: There have been a lot of impressive

movies that have been done in the Boston area. Especially in the late 1990s,

when independent film was booming and money was easier to find, a lot of very

interesting movies were made. From Monument Avenue to The Blinking

Madonna and Other Miracles, I wanted to remind people of these movies. It’s

also my hope that, given the tax breaks and the financial cycle, there will be

more good, locally made movies.

JMG: You mentioned that, in a film such as Down

to the Sea in Ships, the Boston area offered something to filmmakers that

they could not recreate elsewhere. What is the most attractive thing that

Boston offers to filmmakers?

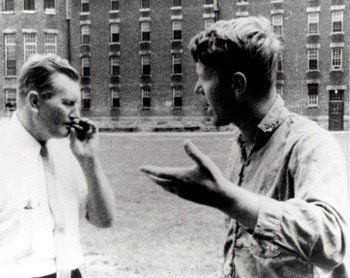

Boston through the lens of Billy and the

Lowlands.

[Click to enlarge]

Sherman: There are two separate beings: films that

locals make, and films by people who come from elsewhere. Indigenous films are

typically more authentic, but it’s not as if there’s a fine line of

distinction. It’s what makes a movie like The Departed so good.

Screenwriter William Monahan, who adapted the story, was a local. He took a

great Hong Kong thriller and gave it a great Boston overlay and ethnic

infusion.

What Boston filmmaking has brought to Hollywood is a

mixture of old and new. Boston films of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s put an

emphasis on Boston’s academic and medical worlds, such as in Coma or

Blown Away. Thankfully, Boston filmmakers look beyond this today, as these

worlds have become cliché. Even as far back as the 1930s and 1940s, Boston was

shorthand for a stick-in-the-mud and a real party pooper. Nowadays, Boston

offers everything to everyone with its tax breaks. Even so, Boston filmmaking

seems to be in a transitional period, and it will be interesting to see the next

phase for the city as a filming location.

JMG: How did you do the research for your book?

Sherman: Many of the movies were ones I had already

covered through the years. Most of them I learned about while they were being

made or released. Through the years, I developed a first-hand knowledge of what

was going on around town. I also tracked down media coverage of the films that

predated my time as a journalist. There was plenty of Internet searching, and

even visiting the locations at which these films were shot. Sometimes, I was in

even in touch with the filmmakers themselves.

JMG: In your book, you attempt to define what makes

a Boston movie. Aside of course from the setting, have you discovered any

common plot or character themes inherent in what you would describe as a Boston

movie?

Sherman: If you look at movies that really nail

things as far as dramas, like Monument Avenue, The Departed, Mystic River,

or Gone Baby Gone, it shows people who are truly stingy with their

emotions and have a chip on their shoulders. The Farrelly brothers really nail

that smartass, New England humor. The most authentic Boston movies don’t

sugarcoat anything. A movie like The Friends of Eddie Coyle doesn’t once

try to paint a scenic picture, and it works. This is also why Hollywood

comedies that are shot here are often unsuccessful.

JMG: What attitude changes, in a political and

artistic sense, make Boston filming more attractive than it has ever been

before?

Sherman: It always helps to have a good and popular

movie like The Departed. You also have those 1990s films such as

Monument Avenue and Next Stop Wonderland that keep Boston on the

fringe of independent filmmaking. Having popular movies like Mystic River

and The Departed certainly help draw attention to the city, but not as

much as tax breaks. It’s still the bottom line that counts more than anything

else. Before the tax breaks, you had the Farrelly brothers shooting in Toronto,

and even parts of The Departed were still shot in New York. If another

state offers a better deal, then productions simply won’t come to Boston.

JMG: You seem to have a lot of respect for

filmmakers who not only shoot in Boston, but especially for those who invest

time and energy into the smaller details, such as character names with local

significance, or whether Boston accents are convincingly portrayed. What else

do you look for when analyzing a Boston-based production?

From The Dark End of the Street.

[Click to enlarge]

Sherman: It’s easy to spot authenticity. In a movie

like Good Will Hunting, when they talk about Kelly’s and T passes, you

have the feeling that they know what they’re talking about. There’s nothing

worse than a Boston movie in which they call Boston Common, “Boston Commons.”

Then there are the movies that come to Boston for nothing more than a generic,

pointless, postcard moment, such as the walk in the North End in Mrs.

Winterbourne. It’s cliché and it doesn’t add to the movie any more than a

walk by Philadelphia’s Independence Hall would have. Movies that have the

details right, like The Departed and The Friends of Eddie Coyle,

are more interesting. Plenty of movies fall into that generic picture of New

England, portraying it as bookish and full of antique stores. Anyone who spends

any time here knows that it’s not all a glossy greeting card.

JMG: You give a lot of credit to films like Jan

Egleson’s Billy in the Lowlands and The Dark End of the Street for

legitimizing production in Boston. Has the American film landscape changed as a

result of Boston films?

Sherman: I don’t think I could pinpoint any changes

that Boston movies are single-handedly responsible for, but films like Billy

in the Lowlands and The Dark End of the Street have certainly helped

to create independent film as we know it today. As Hollywood has become more

hit-oriented, it makes it all the more important for there to be a thriving

grassroots film industry. I give films like The Dozens credit for being

part of the independent movement and for helping to inspire the resurgence of

indie films that continues to this day.

Sherman will be appearing at the Remis Auditorium at the

Museum of Fine Arts on Saturday, May 3rd for a screening of Frederick

Wiseman’s formerly banned documentary Titicut Follies. For more

information about Big Screen Boston, visit

www.bigscreenboston.com.