Picturing the Past

Written by Vikki Warner | Posted by: Anonymous

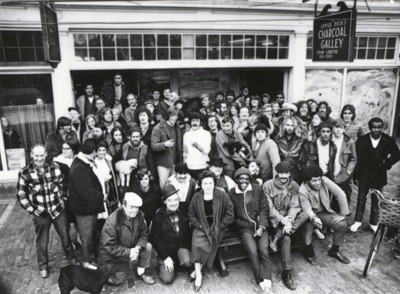

There’s a photo that’s been circulating around Nantucket for 30-odd years now. It was taken on the last day that a local bar and community focal point, the Bosun’s Locker, was open for business, and it depicts 50 or so faces, some introspective, some gregarious, some young, some old, all posed on Main Street in front of the bar. At that time, circa 1970, the beginnings of a shift in the town’s demographics were coming into being. With the closing of the Bosun’s Locker, a popular local hangout was lost, and a little piece of community died.

John Stanton has seen that photo intermittently over the years, and has always had an affinity for the charmingly gruff folks pictured there, many of whom he still knows. Among the flannel, knit caps, jeans and peacoats, there is palpable good nature and friendliness. This version of Nantucket was downtown-based and solidly working-class (with affable mixing between blue- and white-collar folks), and kept local people tightly knit and deeply connected. Today, the Bosun’s Locker’s former space is an art gallery, and shiny SUVs whiz by, carrying transplants and tourists to elegant homes and fancy condominium rentals.

Something about the attitude of that old photo made Stanton want to detail the changes that have enveloped Nantucket, and to pay homage to the old, simpler Nantucket way. The Bosun’s Locker — lively, irreverent, scruffy — was the perfect metaphor. "Last Call: Dreams, Main Street and the Search for Community" (2002, 60 min.) is Stanton’s directorial debut and a universal statement on the beauty of everyday personal interactions.

VW: How did you start filmmaking, and what are some of your other projects?

Stanton: I started out as a newspaper reporter, and I woke up one morning and didn’t work at The Boston Globe, and I was getting to be 30. I happened to get a call from a childhood friend of mine named Bob Quinn. He was a filmmaker in New York. And he had shot a bunch of film footage in Peabody, which is my hometown. By then I was working as a carpenter down here in Nantucket. And he asked me if I wanted to get involved in trying to write a script for this film they were shooting but they didn’t really have a grasp on the narrative. I said, "OK." They assured me it was OK to make a mistake because there was no money involved. Through a friend of mine, we got Studs Terkel to narrate it. That film was called "Leather Soul," because it was about the leather tanneries in Peabody.

Bob and Joe [someone he knew] had a company called Picture Business in New York. The only actual talent I had to offer was interviews. We did a lot of industrials, a lot of corporate work, and we then got an offer to do a film on college basketball in the 70s. It was called "Unfinished Dreams," and it did very well. Slowly, through doing industrial work, I was able to learn how to produce, how to direct. Those guys were very generous in letting me be part of everything. In between all of that, of course, I was shingling houses and painting trim, trying to make ends meet like everyone else. Especially down here, it’s sort of the Nantucket way to be doing four things at once.

I decided to split the director credit with Henry Ferrini, who came on as the cameraman and editor [of "Last Call"], but he’s so much of a creative partner. You’d have to be insane to think one person made a film anyway.

VW: How did the concept for "Last Call" come about? How did you decide this is what you wanted to make a film about?

Stanton: I’ve lived out here on Nantucket for maybe 16 or 18 years, and even since I got here, there’s been so many changes. I just can’t get that newspaper reporter, chat-with-people-all-the-time-and-ask-them-questions thing out of my head. So the more people I spoke with, the more stories I heard about how different it was, not just from the old-timers, but from guys my age — it made me realize that things had changed so much. You get 10 or 12 ideas, and if an idea doesn’t have a subtext, doesn’t have a strong enough central metaphor, you play with it for awhile and then you throw it away. So this one stuck. And I think it stuck because I kept hearing similar stories from other places. I think more and more of this is happening across the country. And so I thought this would be a good way to get at it with some humor. I had heard stories of this bar, and I thought, well, maybe it’s time to start putting together a film. So you start and you stop and you start, and I don’t think anybody in the documentary world starts with a fully loaded budget. We shot it on and off.

VW: The Bosun’s Locker is a metaphor for the way things used to be, and it’s a nice central point from which to anchor the film. How did you decide on this local bar as the center and have the other points play off of it?

Stanton: I knew the guys who were in the picture, and I’d run into them and we used to talk about the old times. Main Street is changing, and we’re losing the concept of Main Street in the United States. Nantucket especially is losing the concept. There’s almost no reason to go downtown, and that’s too bad because that should be a central part of everyone’s lives. I guess I have an affinity for barrooms anyway, but that particular place was the perfect central metaphor. It was downtown. And when it faded, that’s when things started changing here. Those things sneak up on you. Some of those changes are inevitable, and that’s why we used time-lapse. But they’re to be mourned anyway, and they’re to be kept in mind.

VW: You communicate well that so much has been lost. New Englanders are pretty hearty, but it takes a toll every time you experience a loss in the community.

Stanton: We’ve been screening the film here [in Nantucket] and having Q&As afterwards, and then sometimes I’ll go and have a beer and run into people who just saw the film, and they always want to talk about that lost community. And one guy said, "You know, the community’s still here. Isn’t this great? We’re all here. It’s all inside us." But you know, there’s no place for it to come out. You rub up against people in coffee shops and barrooms, and the hairdressers, and the barbershop. There’s a pharmacy that I go to all the time here, Dan’s Pharmacy, and when my kids were young it seems like I was there every day. And I got to know Dan — but from across the counter. I don’t know him enough to have him come over to the house, but I know him enough to pick up the medications and talk about the Red Sox for 15 minutes.

VW: People must have been excited on Nantucket when the film came out.

Stanton: They were, but the important thing is if the central metaphor will hold up off-island. I’ve never done a documentary in my backyard. I know everybody here. The first time I realized what great faces they had. My mother said, "You couldn’t go to Central Casting and get people who look any more perfect." I didn’t realize it until then because I know these people. You don’t look at your friends as characters. One of the things I’ve always tried to do is to go and meet people who are going to be in the story and then put them into a role in my head, so that then I can start constructing the narrative.

I always get antsy about [using academics], because I think somehow it disrupts the narrative. You’ve convinced people to come into this little world where these people live — you’re getting to know these regular people and understand their lives and — boom — here’s an academic telling you what you just saw. I just think regular people have the best insights. It’s much better than you could make up and it’s much better than you could get from a scholar. It’s great when you find people who just talk right from the heart.

VW: For now, you can sit back and enjoy the screening and Q&A process. Any ideas on your next move?

Stanton: This is my first time as director, the first one I actually own. It’s a learning curve about what to do next. I’m open to suggestions, I guess. Susie Walsh, from the Center for Independent Documentary, who was our nonprofit sponsor, was great about coming up with ideas. You need to have somebody who understands what to do next, and who’s seen a number of films go from the process of being a film people liked to gaining a wider audience. I guess that’s the whole point. I’d love to screen it in Missouri or something.

I’ve always thought that artists should stand next to their work, and be there when people say "What about this? What about that?" Someone at one of the screenings stood up and said, "So what’s the answer?" (I guess meaning what’s the answer to Nantucket having to get back to the community), and I said, "Well, I don’t have the answers — and if I did you’d be insane to listen to them." My only job is to put the pictures up on the screen that make you think.

Screenings of John Stanton’s 'Last Call: Dreams, Main Street and the Search for Community' will be held at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts on Friday, October 18 at 6 p.m. and Saturday, October 19. Tickets ($9, or $8 for students, seniors, and MFA members) may be purchased at the MFA Box Office, or by calling (617)369-3770. For more information, please visit www.mfa.org.