Reconstructing the Romanian Past

Written by Maria Luisa Gambale | Posted by: Anonymous

In 1959 communist Romania, the "Ioanid Gang" bank heist was etched into Romanian history. The event was one of the most controversial political cases in the history of communist Romania. The fantastical crime, the arrest of six prominent Jewish intellectuals and former communist activists, the closed trial, and the execution of five men, created a tremendous sensation in Bucharest.

The Communist Party arranged the shooting of a feature-length propaganda film about the heist called "Reconstituirea" (re-enactment). Instead of professional actors, the six convicts themselves were forced – either drugged or lured by false promises – to re-enact the official version of their own crime and arrest on film.

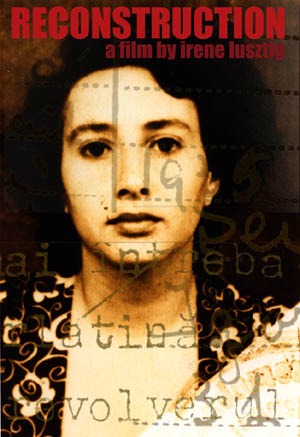

One of those convicts, Monica Sevianu, was the grandmother of filmmaker Irene Lusztig, whose new film, "Reconstruction" will be premiering at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston this month. Irene was the recipient of a 1997 Gardner Traveling Fellowship for young artists, which she spent living in Bucharest, learning Romanian, and shooting "Reconstruction," her first feature-length documentary.

"Reconstruction" examines the events of a story that has been suppressed by the Romanian government for over 40 years. It is both a touching family story, spanning three generations, and a larger examination of present day Romania.

MG: What’s the earliest version you ever heard of the story?

Lusztig: I was 11 or 12… it had been a secret till then in our family. My mom told me because somebody’s parents were in town from Bucharest. I think one of them had been Economic Advisor in the 50’s in the Gheorghiu-Dej regime. They were talking about living in the 80’s in Bucharest and they were complaining how they couldn’t buy enough meat or something. And that, in proportion to some of the things my mother had gone through, I think made her get incredibly upset.

And so, in the car ride home, she just started talking about it. I don’t think she told me the whole story at that point. She told me those people had been really big in the government and the government had done horrible things to her parents. I found out that her stepfather had been shot and that her mother had been in prison. I certainly didn’t know about the film until I told my mother I was going to make a film.

MG: And that film was…

Lusztig: "Reconstituirea"…it’s used in my film, dispersed throughout. It was made by the Ministry of Internal Affairs in 1961, about two years after the bank robbery. It was essentially an educational propaganda tool, in which the bank robbers, in a gruesome re-enactment, are forced to act out the government’s version, the propaganda version of what happened.

MG: When you heard the story, was it something you immediately thought you’d want to tell in a story or a film?

Lusztig: There are a lot of stories I was interested in. Part of it was my grandmother, who was always narrated to me as this colorful character. Part of it was that my mom didn’t write, my mom doesn’t have a language. So, there’s been this deflection of who was going to tell the family story. I wanted to make a movie about the family history, but take my mother’s stories and tell them in some form that my mother herself wouldn’t be able to do. She says she doesn’t know English well enough and she doesn’t like Romanian, so she doesn’t have a language of expression.

MG: Okay, how would you describe your working process while shooting?

Lusztig: It’s pretty loose. I think in some ways what I do is closest to what anthropologists do, how they prepare for their fieldwork. The premise of "I’m going to make a movie and move there for seven months and learn the language" is not standard. I also never have a script. I write a lot, though. I write constantly when I’m there and I write when I watch stuff that I shoot. Both in this film and in "For Beijing With Love and Squal," the writing has ended up being really important to the film. Even in terms of remembering things that I felt while I was there.

In terms of what I’m shooting, it’s really instinctual, but also really messy. With both films, though, I’ve been really surprised which of the random things I shot on instinct or on whim did end up in the movie. And I’m glad I got those things because if I hadn’t, I would’ve had nothing visual later on when I needed it.

MG: And your editing process? Sounds like it will be a similar answer.

Lusztig: Very loose. It took three years, because it changed so much while I was editing. I didn’t want there to be any voiceover at the beginning and now it’s become very voiceover-driven. Without it, it was just too clumsy. My very original inspiration for the film was this book, "Group Portrait With Lady," by Heinrich Böll, a German writer. It’s a portrait of a woman who’s an absent protagonist, much like my grandmother in this film. The structure of the book is faux interview transcriptions with witnesses who knew this woman in one way or another. Somehow by putting that all together, it draws this incredible picture of this woman, whose voice you never actually hear in the book. And of this bigger tapestry of post-war Germany. I really like the idea that by putting together these fragmented narratives, you can form something both about a person and about an era. So, that was sort of my approach.

And then when I did it, of course, it turned out to be a lot messier than I thought and didn’t add up to anything. It really needed a voice of synthesis. And that really had to be my voice.

MG: Are you as a narrator a more reliable witness?

Lusztig: I try not to be. And that was the biggest reason why I didn’t want to have my voice in the film — because I was really afraid that that would undermine the whole premise. I hope that’s not true of the film. I spent a lot of time writing specifically to make a voice that was speculative and uncertain and not declarative. It’s definitely an issue, but it was an issue I was aware of while I was writing.

MG: Now, just in terms of your grandmother. You only met her once when you were little and she’s the subject of your whole film. What was it like for the past four years working with her life history and her image and her legacy? Did it make you feel closer to her?

Lusztig: It’s sort of a strange premise to make a portrait of someone you don’t know. I think it actually brought me closer to my mother more than my grandmother, just by creating this footage where my mother comes to terms with something. In some ways, it was really collaborative. She hadn’t been to Bucharest since she left in her twenties, and she came to help me make the movie. And a lot of the interviews she did was stuff she had never told me and probably hadn’t thought about for a long time or ever. Ostensibly, she thought to herself she’s doing it for me because I was making a movie. But I think it got her somewhere too and to that extent, it was a collaboration.

MG: In terms of your forming influences, who are your most important mentors and why?

Lusztig: Well, all the people at Harvard: Robb Moss, Alfred Guzzetti, Ross McElwee. But probably more than that, Dusan Makavejev. My really basic ideas of what’s cinematic come from him. The basic idea of having faith that you can put two unrelated things next to each other on screen and if you believe they’re related, or they go together, or create a meaning together, than they do. The idea that you can make connections because you, the filmmaker, believe in them, and that’s good enough.

MG: As far as thank-you’s go….some guy in the New Yorker just wrote about all the albums in the Billboard Top Ten. And he realized that all the bands, ranging from nubile country singers to hardcore rap stars to Destiny’s Child…all of them thanked God first in their credits. So, if you had liner notes, who would be on your list?

Lusztig: I actually have to admit that I spend an embarrassing amount of time imagining my credits. I don’t think you’re supposed to say that. But it’s one of the few things that has potential to cheer me up when I’ve been editing forty hours straight. It’s a metaphor for completion.

But I don’t think I’d thank God first… maybe Stalin.

'Reconstruction' will have its premiere screening at the Museum of Fine Arts on Saturday October 6, 2001 at 6:00 p.m. For more information, go to www.mfa.org.