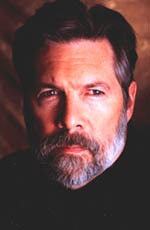

Simple Math: Novelist Lew McCreary’s ‘The Minus Man’

Written by Keith Wagner | Posted by: Anonymous

Hollywood is not kind to screenwriters. "They are regarded as chronic malcontents, overpaid and undertalented," writes John Gregory Dunne in "Monster," his chronicle of writing for the film industry. Jack Warner of Warner Bros. was more succinct in his appraisal of screenwriters: "Schmucks with Underwoods."

At least they’re allowed through the door. The source writer–the author whose novel or story is adapted into a screenplay–fares even worse. Dunne-the-screenwriter assiduously avoids talking to source writers, just as Dunne-the-novelist avoids contacting screenwriters adapting his work, noting "no author likes to hear about the changes the scriptwriter is making." Once Hollywood buys your story, it seems, you’re out of the picture–it’s theirs to manipulate in whatever way they choose.

Lew McCreary, a writer and magazine editor who lives outside of Boston, has certainly heard these horror stories. He might have expected the worst when his 1991 novel "The Minus Man" was adapted for the screen by Hampton Fancher, whose screenwriting credits include the sci-fi classic "Blade Runner." "Usually, they tell the writer to go screw," McCreary said during a recent telephone conversation. But in this case, the screenwriter was willing to involve the author throughout the entire process, up to and including an invitation to the film’s premiere at Sundance–altogether "an exceptional and atypical experience," as McCreary describes it.

The two first met in the summer of 1995. Fancher, armed with pages of single-spaced notes, came to visit McCreary at "CIO Magazine" in Framingham, where the author is editorial director. They camped out in a conference room and got to know one another over a long and far-ranging conversation about the book. "I liked him immediately," McCreary says. "I trusted him and knew that I would like whatever he would do with the book." Fancher says he was "astounded" by McCreary’s writing, and welcomed his involvement in the screenplay.

McCreary, however, harbored no illusions. "I’ve been around long enough to know that for every 100 books optioned, only one gets made into a movie," he says. "But I figured, What the hell? This is going to be fun. Working with Hampton was going to be its own reward."

Fancher wrote the screenplay in about five months, and sent McCreary a copy as soon as he was finished. "I wanted to stay tuned to his reactions," Fancher says by phone from New York, "and if he had bad reactions, I wanted to change them. As it was, we were very in tune." Further conversations followed, on the phone and in person ("There even may have been a letter or two," says Fancher). Ideas and opinions were solicited; some were adopted, like McCreary’s rewrite of a high school football scene–"Hampton indulged me, since he doesn’t know a thing about football." In the end, little was added to Fancher’s first draft.

McCreary was even kept informed about casting decisions, which included his own–he was given a bit part in the movie as a businessman who meets an untimely end in a diner. "I like the idea of his creation killing him," says Fancher, who also directed the film. "It’s kind of Doctor Frankensteinian." Before filming, they ran through the scene a few times, and McCreary recalls his final direction from Fancher: "When you knock the cup over, try not to look like you’re doing it on purpose." They filmed the shot in one take.

McCreary was even kept informed about casting decisions, which included his own–he was given a bit part in the movie as a businessman who meets an untimely end in a diner. "I like the idea of his creation killing him," says Fancher, who also directed the film. "It’s kind of Doctor Frankensteinian." Before filming, they ran through the scene a few times, and McCreary recalls his final direction from Fancher: "When you knock the cup over, try not to look like you’re doing it on purpose." They filmed the shot in one take.

The novel, McCreary’s second, is both a "youth grows up and leaves home" story and a "stranger comes to town" story, moving back and forth between the present and flashback. Vann Siegert, our protagonist, travels cross-country for a fresh start and ends up in the fictional town of Bledsoe, MA, settling into a room he rents from Doug and Jane Dean. But he brings some pretty dark baggage with him, which has an enormous impact on the community. It’s a beautiful book, fast-moving despite its sparse action–"a page-turner without something happening," in Fancher’s words–and wonderfully, vividly written.

"I had a tender reaction to it in terms of character," Fancher says of the novel. "These characters had life. They spoke for me, or to me. I always try to achieve a terseness [in my writing], an ellipticality, and that was present here." Also present were other themes that Fancher is interested in exploring in his work–loneliness and isolation, the dark part of human nature.

"If you adapt a book, the book and the screenplay bear about as much resemblance as an egg and an omelet," Fancher says, so changes were inevitable. In "The Minus Man" the most obvious change is setting, moving the action from Bledsoe to an equally fictional town in the Pacific Northwest. This may have been as much a financial consideration as a creative one–McCreary speculates that a location shoot may have been prohibitively expensive for an indie-film budget.

This change, though, didn’t have as much impact on McCreary’s story (or Vann’s) as Fancher’s desire to focus on the "stranger comes to town" story–a tricky proposition, especially in a novel where past and present seem inextricably linked. But the "now" of the story was what interested Fancher, the character of Vann, "a man without purpose who’s doing things purposefully."

What to do, then, with all that historical flashback? You don’t necessarily need it–a film about how one man’s arrival causes a small community to unravel, like "Bad Day at Black Rock," would be interesting enough. But back-story adds depth, and Fancher integrates this material cleverly. In the novel, Vann imagines being interrogated by detectives, and Fancher includes these characters in the film, playing out their imagined conversations. Through interviews and voice-overs, the detectives (Dwight Yoakam and Dennis Haysbert) become the vehicle for introducing historical information about Vann (Owen Wilson). Fancher says the detectives were interesting characters to work with, because they’re essentially parts of Vann, acting both as his conscience and paranoia. "They threaten him, let him know he’s flying a little close to the flame."

So contrary to what John Gregory Dunne might have us believe, sometimes both parties walk away from an adaptation feeling good. Of the many projects he’s scripted, "this is the one that I enjoyed the most while writing," Fancher says. "I had a vision when I was finished writing the screenplay, and that’s what the film turned out to be, without a hitch, clear and simple."

McCreary also seems pleased with the film. "Owen Wilson did a remarkable job of conveying a type of charm, drawing you in, but he’s always making you regret it," says McCreary. The worst he has to say about the experience is that the premiere screening at Sundance was "anxiety provoking" (that and having to eat "the coldest french fry I’ve ever eaten in my life" while on the set). What’s more, he’s been inspired to try his hand at a screenplay of his own.

"Even if it hadn’t gone on to be a movie," says McCreary, "it still would have been great for me. All in all, it’s been a kick." And that, ultimately, is what making movies is supposed to be about.

'The Minus Man,' starring Owen Wilson, Brian Cox, Mercedes Ruehl, and Janeane Garofalo, opens in theaters September 24. Lew McCreary's novel will be republished by Grove/Atlantic Press and available in September. You might be able to find it sooner through BarnesandNoble.com even though it is out of stock.