Company/Organization Profiles | Local Industry

Squigglevision: Fun and Good for You

Written by Keith Wagner | Posted by: Anonymous

When was the last time you watched Saturday morning cartoons? Me, I was parked in front of the tube only this weekend, but I wasn’t vegging out under a 30-minute barrage of animated product placement (and I use "animated" more to describe technique than content). I was watching "Squigglevision," which has returned to ABC for a second season this fall, sporting a new format and new characters, and between laughs I was learning stuff.

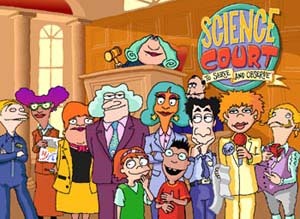

"Squigglevision" is created by Tom Snyder Productions (TSP) in Watertown, MA, home to Comedy Central’s hit series "Dr. Katz: Professional Therapist." At the heart of "Squigglevision" is "Science Court," a courtroom drama illustrating principles of physical science. Each week some accident or crime occurs, and fortunately for the slighted party, attorney Doug Savage (voiced by comedian and co-writer Bill Braudis) is there to take up the case. The defendant retains the infinitely more science-minded Alison Krempel (Paula Plum), and Judge Stone (comedian Paula Poundstone) presides over the proceedings.

Consisting exclusively of "Science Court" last season, the show now contains three educational components: science, which receives the most attention; math, presented by Professor Parsons (expert witness for the defense in "Science Court," voiced by comedian Jon Benjamin) in the segment "See You Later Estimator"; and vocabulary, in the word-of-the-day segment "Fizz and Martina’s Last Word."

"Squigglevision" has "the kind of incredibly obvious silliness that appeals to kids and adults," says Braudis, who co-created the show with TSP founder and chairman Tom Snyder. Snyder also shares the writing duties, producing a short treatment that details the science involved and how the story plays out. He builds his stories around simple experiments kids can do at home, then "reverse-engineers a crime around it, usually involving Doug making a false accusation." From there, Braudis fleshes out the story into a three-act script, usually in one week. "Sometimes it takes longer, because I have to go to my encyclopedia and relearn the science," admits Braudis. Because they don’t write down to the audience, the show doesn’t come off as condescending. In this regard, Snyder has created the show he hoped to, one that parents can enjoy alongside their kids, a contemporary "Rocky & Bullwinkle."

There’s a maverick feel to things at Tom Snyder Productions. Take "Squigglevision’s" origin, a story of fortuitous coincidence with the makings of modern myth. Two years ago, riding the success of "Dr. Katz," Snyder sold a pilot to DreamWorks, but when studio execs wanted to alter the show, Snyder said "no way." The deal foundered, and Snyder returned to Cambridge with an entire animation crew in tow. "Science Court" was born late one night at a local Chili’s during the O.J. trial. Snyder heard "everyone in the place talking about DNA evidence, which is very complicated science." The courtroom, he realized, is a great place to introduce ideas dramatically. And the timing was perfect: in August 1996, the FCC had ruled that TV stations must provide three hours of educational programming per week, so the networks would be starving for quality programming.

Snyder, who taught science in elementary school for ten years, had been wanting to make an educational TV program. And physical science, with its cause and effect, has tremendous visual appeal. That’s what drove "Watch Mr. Wizard" on NBC through the ’50s and ’60s, and spurred its reappearance as "Mr. Wizard’s World" on Nickelodeon in the ’80s. The experiments science teacher Don Herbert whipped up in his kitchen made for great viewing. And so it is with "Science Court."

Squigglevision, initially the name of the animation technique Snyder created, multiplies the possibilities for the show. Unlike conventional animation, it’s fast, easy, and technically uncomplicated. "There are almost no disadvantages," says Snyder. "It costs just as much to do a helicopter scene as it does to do a living room scene. And you have enormous range – you can take the entire jury to the North Pole if you want."

"We’ve made a religion of having a character sitting in a chair, squiggling," says producer Loren Bouchard. The animation seems hyperactive, but actually practices what he calls an "economy of motion." Instead of going frame to frame, five similar but slightly different drawings are run in loops called "flicks," giving the image its vibrating quality. The crew then uses the Avid as an animation tool, assembling these flicks to the finished audio track. "It’s the most simple form of animation raised to a higher level by filmic considerations," Bouchard says. Quite different from the computer-generated characters in Pixar’s "A Bug’s Life," which in some instances took 84 computers 24 hours to produce one second of action, according to "Wired" magazine. "We’ve invented a system that allows a small number of people to work at something without nitpicking it to death," says Bouchard. "It’s more like being in a rock band than working in an animation studio."

"Squigglevision’s" variety-show format was a request from ABC; the network thought the science too dense, too daunting, for the 8-to-14 Saturday morning crowd, an audience often accused of having stunningly short attention spans. Snyder had already anticipated as much. "We had started scaling way back on the amount of information after the first two or three shows," he says, because they overestimated the age of their actual audience. The stripped-down "Science Court" has "less hard science and more context for the science that’s going on."

Also at ABC’s request, TSP is "retrofitting" last season’s 13 longer "Science Court" shows, trimming the courtroom story and adding new material. Considering that "Squigglevision’s" three audio editors can piece together a 22-minute episode from 35 minutes of recorded dialogue –"Like Betsy Ross," says editor Paul Santucci, "but without the comfy rocking chair" – Bouchard says "cutting it down to 17 minutes is a walk in the park." Their mission: protect the court story, protect the science, keep the funniest jokes.

The maxim "less is more" best describes the TSP work ethic. With just 95 people, their primary business is making interactive educational software which works on a one-computer-per-classroom premise, thus encouraging collaboration and interaction among students – just the stuff kids need to succeed in the real world. The Squigglevision team has only 16 members, yet they produce two nationally syndicated animated series. And of course, there’s the littlest expert witness for the prosecution, the ever charming Dr. Julie Bean, voiced by Snyder’s daughter Amy.

While Watertown isn’t the first place you’d look to for network programming of such exceptional quality, 100% of the production is done under the TSP roof, with recording, editing, and animation facilities. An episode of "Squigglevision" can be completed in 10 weeks, whereas conventionally animated shows can take upwards of 18 months to produce. "L.A. is not thrilled for people to find out you don’t need to be in L.A. to make a cool show," says Snyder. "It kind of pricks the myth of L.A. being the place where the talent is."

In the brash and polished world of Saturday morning children’s "advertainment," the raw enthusiasm of "Squigglevision" provides a wonderful novelty, teaching rather than selling kids something. Snyder has created a show with integrity and vitality. Asked about a third season of "Squigglevision," Snyder says, "I would love to write another 13 of these crazy things." We should all be so lucky.

'Squigglevision' can be seen in the Boston area Saturdays at 10:30 a.m. on WCVB, Channel 5.